As I was writing my biography of Mathilde Blind, I fretted over how to write about her erotic life. While I often comforted myself by repeating John Keats’ formulation like a mantra, and dwelling “in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason,” I also wanted to interpret the available evidence in order to tell the fullest possible story of her personal as well as literary passions. At an early stage in evaluating that evidence (her letters, her autobiographical fragment, her poetry and prose, and the letters and memoirs of her friends), I formulated a crude working hypothesis: while Blind was attracted to certain men’s minds, and their professional connections, it was women–their minds and their bodies–who most deeply stirred her.

Even this formulation was unsatisfactory, though, because it nudged me toward a binary (gay vs. straight) that didn’t seem quite right. Unlike her friend Vernon Lee, all of whose most passionate relationships were with women, Blind openly admired, and spent considerable time with, men like Richard Garnett, Ford Madox Brown, and Arthur Symons. The latter even claimed that her poem “Scherzo” in Dramas in Miniature (1891) expressed her unrequited passion for him (see my analysis of this poem below, which resists this heterosexual pigeon-holing). But like Lee, Blind also had passionate attachments to women. These ranged from her childhood friend Lily Wolfsohn to her New Woman colleague and friend Mona Caird, who accompanied her on a country idyll that produced some of Blind’s most sensuous descriptions–of feminized and erotically charged landscapes. Like this one, from Blind’s Commonplace Book, describing a walk she took with Caird:

Walk to the twilight wood on the hill-side with the silvery broken light on the barley field. We were struck by the singular outline of a hornbeam with the trunk + branches half thrown back curiously resembling a woman’s body. It might have been some female struggling passionately to escape pursuit. Yea, Daphne herself changing into a shrub. (fol. 24-25)

For Blind and other New Women poets, female sexual desire unmoored from marriage–and from compulsory heterosexuality, to use our contemporary currency–constituted a radical declaration of independence.

Which explains the title of this blog. “Queering,” according to Eve Sedgwick, seeks an “open mesh of possibilities” (8) to disrupt traditional binary epistemologies that are constructed as oppositional and interdependent. By contrast, queering seeks fluidity, dissonances, gaps, and excesses of meaning that materialize “when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically (8). This comes closer to describing my sense of Blind’s radical ideas about gender and sexuality than terms like “gay” or “straight.”

Perhaps I should have written an additional chapter with the title of this blog. Or perhaps another scholar will write a book about Blind bearing this title.

I’ve been thinking about these issues ever since reading Susan David Bernstein’s review of my biography in Review 19 (which is thorough and incisive, despite the quibbles I am about to share). Gregory Tate, in his Review of English Studies essay, called my “determination to stick to the facts, . . . for the most part, admirable,” but added that “the shortage of speculative interpretation can also be vexing. (He is specifically referring here to my reluctance to speculate on the reasons for the serious quarrel between Blind and Ford Madox Brown in August 1882.) Bernstein, on the other hand, suggests that I go too far in speculating about the erotic elements in Blind’s relationships with Garnett and Caird. About Garnett:

Diedrick dubiously claims that [several men’s] relation to her was implicitly sexual. Interpreting her response to Garnett’s request that she read the draft of a story he sent her, Diedrick writes: “In accepting this invitation to literary intercourse, Mathilde would be taking the story into herself, commingling with Garnett’s imagination, imaginatively becoming one with him. Throughout this period in their relationship, sex is often an implied subtext in their exchange about texts” (57).

(I do need to note here, as I do in the biography, that Garnett specifically suggested (and suggested suggestively) that Blind take his story–”The Firefly”–and translate it into German, and that the result “would benefit us both, and it would be great fun to see the thing in German dress”).

And about Caird:

During her travels with Caird, Diedrick speculates, the two were briefly lovers until Brown’s imminent death recalled Blind to London. Just as Diedrick earlier found erotic evidence in Blind’s correspondence with Garnett, he also finds it in her commonplace book: “Her entries,” writes Diedrick, “speak of an intimate communion with Caird, both physical and mental” (228).

(Yes, but: I don’t call Blind and Caird “lovers,” and I meant the word “intimate” to remain suggestively ambiguous.)

In writing about these events in Blind’s life I hoped to convey several things. First, that certain men were erotically as well as intellectually attracted to Blind, even though there is scant evidence that she reciprocated the first of these two attractions. Second, even without the kind of evidence leading some to call Vernon Lee a lesbian, it is important to show that Blind felt and expressed (obliquely in some of her poetry, less so in some of her autobiographical prose) erotic desire for women. Moreover, I wanted to demonstrate that although she remained resolutely single (her antagonism toward marriage was notorious, and often expressed with wonderfully mordant humor), her poetry and prose speak of a deeply passionate life–although the precise objects and outcomes of her passions leave us in “mysteries and doubts.” Her abiding attachments to the men and women who enriched her life intellectually, emotionally, and physically (the latter at times by the “mere” fact of their physical presence and proximity) are at the core of her life story.

And central to what we might call her “queerness,” in a somewhat more broadly cultural sense than what Sedgwick’s definition above may imply. In her introduction to her translation of Marie Bashkirtseff’s journal, Blind links Bashkirtseff directly with her friend and fellow poet Rosamund Marriott Watson, whose exercise of sexual freedom had made her notorious in many circles. Describing Bashkirtseff’s unrepentant hedonism, Blind alludes to Watson’s poem “Of the Earth, Earthy,” a militantly secular paean to sensuous existence: “no rapt and saintly vision clothed in the purity of dawn passes across her vision; this child of the nineteenth century is of the earth earthy” (xii). Blind’s poem “Scherzo” partakes of this same spirit. Its speaker compares her would-be lover (who could be male or female, given the metaphorical gender inversions at work) to Endymion, whose beauty inflamed Diana, and describes her passion in pagan, intensely sensual terms:

You are light and life in sooth,

Fair as was that Grecian youth

Who in her cold sphere above

Drove poor Dian mad with love—

When she saw him where he lay,

White and golden like a spray

Of tall jonquils whose intense

Sweetness faints upon the sense;

When she saw him swathed in light,

Couched on the aërial height

Of hoar Latmos, hushed and warm;

While, to shield him from all harm,

Like a woman’s rounded arm,

A fresh creeper wildly fair

Twined around his throat and hair. (85-6)

The speaker effects an inversion of conventional gender roles in this passage, first by investing the male beloved with qualities typically ascribed to females by desiring males (passive receptivity, purity, sweetness, warmth), then by comparing the ivy that protectively “shields” him to a woman. The penultimate stanza of the poem describes how Diana’s desire for Endymion surprised her, causing her to momentarily forget her reputation for purity: “She forgot in her surprise, / When her empyrean eyes / Saw Endymion where he lay / Slumbering” (75-78). The words immediately following the caesura in line 78, however, emphasize choice and agency, as “she cast away / Her immortal honour, clear / As her own unclouded sphere, / For the palpitating bliss / Of a surreptitious kiss” (75-82). Although she willingly gives up “her immortal honour” to transform herself from a virgin goddess to desiring woman, her embrace of sexuality is not associated with any sacrifice of human honour (her own “sphere” remained “unclouded”) [“‘Hectic Beauty'” 637].

In this sense Diana, like “Scherzo” itself, and like Blind in her life and writing, forcefully represents every woman’s right to gender and sexual self-determination.

Works Cited

Blind, Mathilde. The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff. Translated with an Introduction by Mathilde Blind. 2 vols. Cassell, 1890.

____. Dramas in Miniature. Chatto and Windus, 1891.

____. Commonplace Book 1892-95. Bodleian Library, Oxford (Ms. Walpole e.1.).

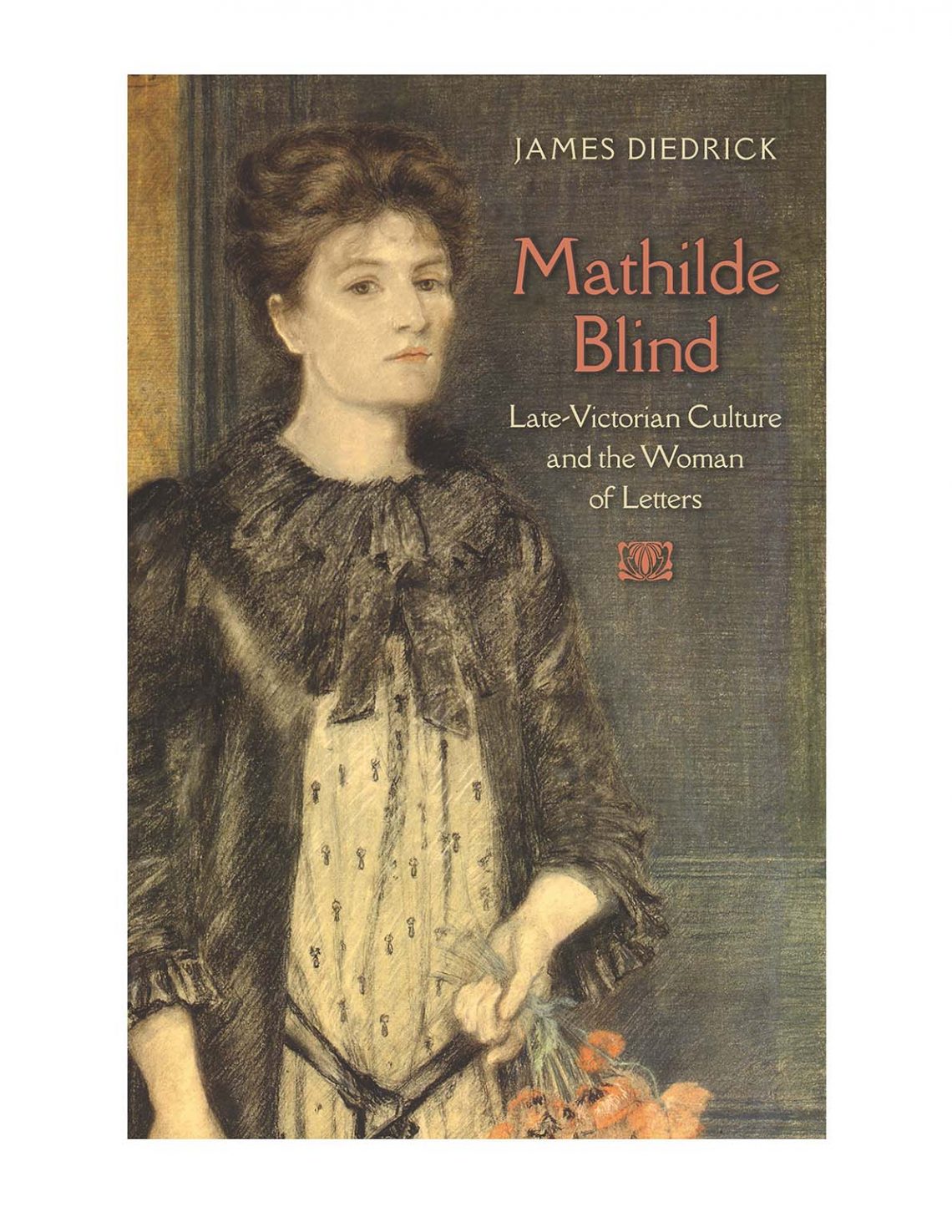

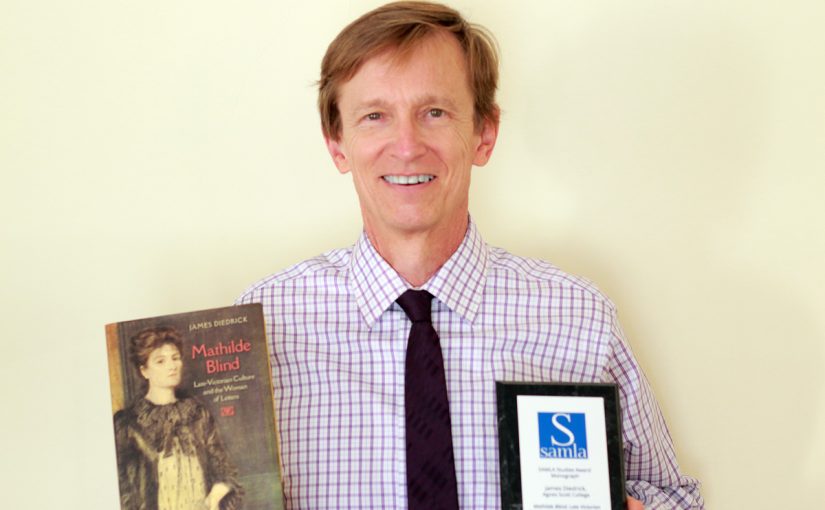

Diedrick, James. Mathilde Blind: Late-Victorian Culture and the Woman of Letters. University of Virginia, 2016.

____. “The Hectic Beauty of Decay'”: Positivist Decadence in Mathilde Blind’s Late Poetry. Victorian Literature and Culture 34 (2006): 631-48.

Sedgwick, Eve. Tendencies. Duke UP, 1993.