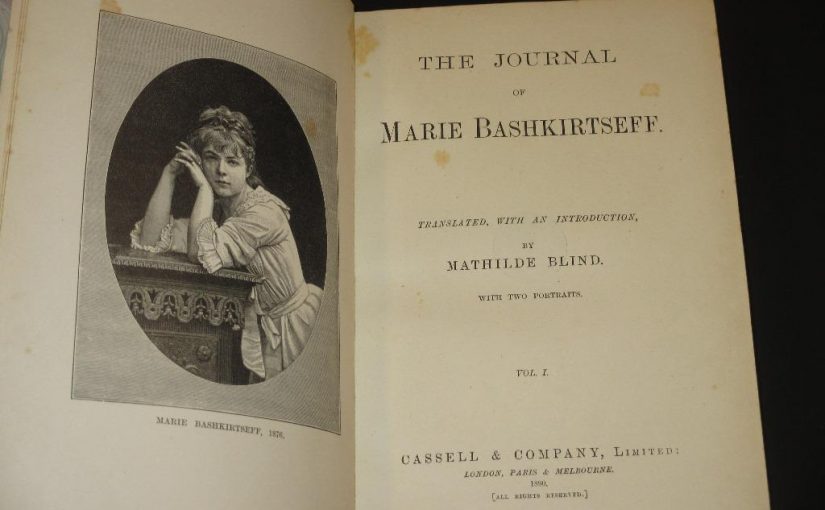

The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff

Translated, With an Introduction by Mathilde Blind

London: Cassell, 1890

Introduction (Vol. I, pp. vii-xxxiv)

[NOTE: Blind’s identity as a New Woman writer is reflected in her poetry, but also in her prose–from her 1878 essay on Mary Wollstonecraft to her 1890 translation of The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff (see “Mathilde Blind’s (Proto-) New Women” for more on this). This translation followed closely on Blind’s two-part essay on the Russian-born painter for The Woman’s World, at the time edited by Oscar Wilde, and it was followed by an 1892 essay “A Study of Marie Bashkirtseff.” The Journal itself became a publishing sensation and intensified late-century debates concerning gender and sexual identity. It also outsold everything else Blind published (it was reissued in 1985 by Virago Press). A proto-post-modernist conception of identity characterizes all three of Blind’s essays on Bashkirtseff, as well as the translation itself. In her 1888 essay, she writes that Bashkirtseff’s journal will be “instructive” and “fascinating” to the student of human nature, revealing its author’s “curious, composite, prematurely developed nature” (352). In her introduction to the translation, she writes that Bashkirtseff “never wholly yields herself up to any fixed rule of conduct or even passion, being swayed this way or that by the intense impressionability of her nature” (I: viii). And in her “Study,” Blind emphasizes the subjective nature of perception itself, doubting whether human consciousness can unproblematically mirror and transcribe an “objective” reality: “we question whether any two people . . . would ever see precisely the same thing. . . . For the artist’s own mind, unlike a photographic apparatus, would always intervene so as to force him to see life through the medium of his temperament” (152). This is one of the sources of Blind’s approach to translating the journal itself, which combines both mediation and interpretation on her part. Blind’s “Introduction” to the Journal, presented here in full, can be considered a major contribution to the New Woman discourse of the Fin de siècle.]

* * * * *

AN autobiography such as this Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff — a book in the nude, breathing and palpitating with life so to say — has never, to my knowledge, been given to the world. In some sense, therefore, its publication may be looked upon as a literary event. To read it is an education in psychology. For in this startling record a human being has chosen to lay before us “the very pulse of the machine,” to show us the momentary feelings and impulses, the uninvited back-stair thoughts passing like a breath across our consciousness, which we ignore for the most part when presenting our mental harvest to the public. Is it well, is it ill done to make the world our father confessor, to take it into our most intimate and secret confidence? Difficult to say, but in any case it is supremely interesting. For it is like possessing one of the much envied fairy gifts which enabled one to see through stone walls and to hear the thoughts as they passed through a man’s head. We may like this book or not; we may find the personality revealed in it adorable or repellent; but no one can deny that it is a genuine addition to our knowledge of human nature. “In any case,” as its young author says, with striking penetration, “it is at least interesting as a human document,” and more particularly so as a document about feminine nature, of which as yet we know so little. Indeed, most of our knowledge comes to us second-hand, through the medium of men with their cut-and-dried theories as to what women are or ought to be.

Now here is a girl, the story of whose life as told by herself may be called the drama of a woman’s soul; at odds with destiny, as such a soul must needs be, when endowed with great powers and possibilities, under the present social conditions; where the wish to live, of letting whatever energies you possess have their full play in action, is continually thwarted by the impediments and restrictions of sex. A girl with the ambition of a Caesar — as she herself says — smouldering under her crop of red golden hair, has a hard time of it though her head repose on down pillows edged with the costliest of laces; such a girl may well be fretted into a fever by the loving care of her affectionate aunts and uncles, and grandparents, &c. &c. [viii] Did we but know it the same revolts, the same struggles, the same helpless rage, have gone on in many another woman’s life for want of scope for her latent powers and faculties.

. . . she is made up of heterogeneous elements, and her mutability of mood is a constant surprise to the reader. She never wholly yields herself up to any fixed rule of conduct, or even passion, . . . .

But Marie Bashkirtseff is too complex and versatile a nature to be taken in illustration of any particular theory; she is made up of heterogeneous elements, and her mutability of mood is a constant surprise to the reader. She never wholly yields herself up to any fixed rule of conduct, or even passion, being swayed this way or that by the intense impressionability of her nature. She herself recognises this anomaly in the remark: “My life can’t endure; I have a deal too much of some things and a deal too little of others, and a character not made to last.” The very intensity of her desire to seize life at all points seems to defeat itself, and she cannot help stealing side glances at ambition during the most romantic tête-a-tête with a lover, or of being tortured by visions of unsatisfied love when art should have engrossed all her faculties. For she wants everything at once — whatever success Fortune has to offer its favourites, the glamour of youth and beauty, rank and wealth with their glittering gifts, the artist’s fame, the power of a queen of society — all, all, or nothingness! She hardly realised in her passionate self-absorption and egotism how much she asked, or what a niggard Fate is to the claims of individual man. I was strangely reminded of her on my return from Paris last autumn, where I had been to see her pictures and the house with its splendid studio where the last years of Marie Bashkirtseff’s life were spent. Near me, on the Calais boat, sat a beautiful little French boy between three and four years old, staring intently at the sea below. Suddenly he looked round and asked, as if the thought had just struck him, “Is this the sea, Mamma?” On her replying in the affirmative, he said in the most matter-of-fact tone, “Mamma, I want to drink up the whole sea.”

“Maman, je voudrais boire toute la mer,” said this delicate, golden-haired mite of a boy, his earnest eyes fixed on the welter of waters just lit for a moment with the stormy crimson of a sudden sunset. This wish — childish but not unnatural where the limits of personality are unrealised — seemed like an echo, the mocking echo of Marie Bashkirtseff’s life.

. . . she was too intensely modern for repose.

Did not she too want to drink up the whole sea, the whole of life, embracing the entire circle of sensations, but finding only a few poor pitiful spoonfuls doled out to her instead, dash herself to pieces, in her ineffectual rage at the obstacles she encountered. How well she knew herself [ix] is shown by her saying, “If I could keep a little quieter I might live another twenty years.” But she was too intensely modern for repose. Born in an age of railways and electric telegraphs, she wanted to live by steam. Terribly moving, when we remember the sequel, is that bitter cry of hers, the very burden of her Journal: “Oh, to think that we live but once and that life is so short ! When I think of it I am quite beside myself, and my brain reels with despair” . . . .

“We live but once, and my time is being wasted in the most unworthy fashion. These days which are passing are passing never to return.

“We live but once! And must life, so short already, be shortened still further; must it be spoilt — nay, stolen — yes, stolen by infamous circumstances?”

This violent temperament, full of stress and tumult, may [x] be partly due to the opposing tendencies of heredity and actual circumstances. For Marie Bashkirtseff, although in a measure the product of modern French life, and moulded by cosmopolitan influences, is nevertheless intensely Russian. Her personality is a singular mixture of untutored instincts joined to an ultra-modern subtlety of brain and nerves. She has the wild Cossack blood in her veins, but on her back the last fashionable novelty by Worth. Her religion offers the same curious compound of primitive idolatry and philosophical reasoning. Not only is she apt, as Mr. Gladstone so happily expresses it, “to treat the Almighty as she treated her grandfather, en égal,” the nature of her prayers is essentially similar to a savage’s worship of his idol — inclined to be extremely devout if his requests are granted; but likely to turn restive and make away with his fetish if the latter remains deaf to him. And the singularity is that while she is acting her religious part with immense fervour, devoutly saying her prayers as she kneels on the floor, she doesn’t believe in God at all. Indeed, she acutely dissects the nature of religious beliefs, while continuing in her half-belief; for, as she says in her naive cynicism, “cela n’engage à rien.” Yet she was full of profound intuitions — unexpected flashes of insight that opened out perspectives into the infinite mysteries of spiritual experience. She startles the reader every now and then in the very midst of her wounded vanities and lamentations over her wasted life of sixteen summers by assuring him that she is not to be taken quite seriously, that, after all, it is not so very sad, and that the sadnesss itself and the sighs, the tears and the wringing of hands, are part of the play at which the other Ego — the over-soul as Emerson would say — is all the time present as at a spectacle. This unknown factor of human consciousness, aloof and indifferent to misery and pain — nay, even enjoying misery and pain — is often referred to by the youthful writer, showing that Marie was [xi] above all a born critic of life — love and sorrow, passion and pain serving but as the raw material for the development of thought and analysis. In this respect her Journal is a far more complete expression of her individuality than her pictures are. And it is possible that the novel — the most modern of all forms of art — might have afforded the fullest scope for the development of her genius. For the novel, treated with the conscientious precision of scientific analysis, is the distinctive feature of Russian literature. But the question is whether she was not too much taken up with herself to enter into other lives with the sympathetic insight required for the delineation of human character. Be that as it may, she has produced a book of more absorbing interest than any novel can ever be — a book with all the attraction of romance, and yet a mirror reflecting life in its passage from day to day. Indeed, the unique interest of this Journal arises from the fact that the writer, in the very ardour of the moment, finds relief in recording her impressions; and while in the act of experiencing a variety of sensations, she is yet able to treat herself, and others in contact with herself, as objects of dispassionate observation, to be used with minute fidelity in the representation of human existence.

In order to understand this composite, abnormal, prematurely-developed nature, it is necessary to have some knowledge of her family and circumstances. Marie Bashkirtseff’ was born at Poltava, in the Ukraine, on the 11th of November, 1860. The vast steppes and stirring traditions of her native land form the appropriate background for this extraordinary child, fall of quenchless ardour and explosive force. Her father, the son of General Paul Gregorievitch Bashkirtseff, was a wealthy landed proprietor, belonging to the Russian gentry, and Maréchal de Noblesse, in the above-mentioned town. In some respects he seems to have been a specimen of that type of Russian noble which Tolstoï has so inimitably portrayed in Oblonsky, the brother of Anna Karénine, the gay Lothario who [xii] makes love to his wife’s governess, and drives poor Dolly to distraction. M. Bashkirtseff, some members of whose family had died of consumption, took to wife a Mlle. Babanine, a tall, healthy, and beautiful young girl, whose family were of older nobility than his own, being of supposed Tartar origin, “of the first invasion.” Marie’s maternal grandfather was a fine specimen of the nobleman of the generation which had been stirred by the poems of Poushkine and Lermontoff. He was enlightened and studious, had written verse in Byron’s style, and served in the Caucasus, and, while still very young, got married to a girl of fifteen, a Mile. Cornelius, who bore him a family of nine children. The union of Marie’s parents not proving a happy one, chiefly owing to M. Bashkirtseff ‘s persistence in sowing his wild oats after marriage, the young wife left him after a few years of wedded misery, and returned to her parents, with her two children, Paul and Marie. They lived all together at Tcherniakowka, M. Babanine’s country house, whose exquisitely laid-out grounds evinced the artistic taste of their proprietor. Marie, then a frail and delicate child, became the idol of her grandmother and of her aunt — the unmarried sister of Mme. Bashkirtseff A fortune-teller, whom Marie’s mother consulted, predicted: “Your son will be like the rest of the world, but your daughter will be a star.”

In 1870, after the death of her mother, Mme. Bashkirtseff left Russia, accompanied by her father, her unmarried sister, her little niece Dina, Walitzky, the faithful family doctor, governesses, nurses, and dogs of various descriptions. They went to Vienna, travelled through Germany, and became henceforth part of that floating Russian population which drinks the waters at Baden-Baden, stakes its thousands at Monte Carlo, and looks upon Paris as its earthly paradise. Thus, from the age of ten, Marie may be said to have begun seeing the world; and she kept her eyes and ears wide open all the time, taking object lessons in life, learning many things which might have been more wisely left unlearned. Glimpses of fashionable [xiii] society at Baden-Baden gave her many a pang of unsatisfied vanity. Yet her thirst for distinction did not suffer her to rest idle. From the age of four, we are told, visions of future greatness had haunted her brain. She imagines herself in turn the first dancer, the finest singer, the most accomplished harp-player in existence; she electrifies masses of men by the magnetism of her eloquence; she dreams of marrying the Czar, and so saving his throne by inaugurating social reforms which shall bless the Sovereign and his people. True, this was in her nursery days, if such days ever existed for her. But, in any case, she is determined to play a leading part on the stage of life.

. . . no rapt and saintly vision clothed in the purity of dawn passes across her vision; this child of the nineteenth century is of the earth earthy, . . . .

Her Journal, the earlier portions of which she destroyed, opens at Nice in January, 1873, when she was twelve years old. It is written in French, as Marie possessed but an imperfect knowledge of Russian. Like most great poets, from Dante to Byron, she was bound to fall in love at this early stage of her existence. But no rapt and saintly vision clothed in the purity of dawn passes across her vision; this child of the nineteenth century is of the earth earthy, and fully alive to the value of a coronet. For she fixed her affections on an English duke, the most conspicuous figure amid the brilliant throng driving along the Promenade des Anglais. It is difficult to make out how much of her adoration is due to the classical features of this horsey Briton, and how much to the faultless appointment of his four-in-hand. Of course, they had never met or exchanged a word, and the noble duke was ignorant of the very existence of this funny little girl in short frocks within whose soul his memory burned like a lamp. A poor ideal at the best for a devotee to kneel before, but such as it was it was kept alight for a couple of years or so, being finally quenched by the announcement of the duke’s marriage, which rudely dispelled the day-dream once for alL Marie suffered agonies for a time, agonies quite different, she confesses, from “what I [xiv] formerly endured when a wall paper or a piece of furniture displeased me.”

But amid the distractions of imaginary love-dreams, of change and travel, this young girl managed to acquire a surprising amount of knowledge. She threw herself into study with the same passionate intensity that marks her life in all its phases. At thirteen she drew up a plan of study which she had thought out as carefully as though she were preparing to take a degree. She learned English, Italian, and German, Latin and Greek, drawing and music. But music was her most engrossing interest at this time, for her magnificent voice might have helped her to realise her wildest dreams had it not been early impaired by the fatal disease which ultimately ruined it. Education in the moral sense of the word — which would have helped to supply that moderation and harmony of the faculties, for want of which she probably perished earlier than she otherwise might have done — she had absolutely none. There was not a member of her family, indeed, capable of guiding or controlling her, and while acquiring knowledge and accomplishments of all kinds with intuitive facility, she remained in regard to moral training as undisciplined as a wild colt of the steppes. She was too keen an observer not to admit some years later that while her family had spoilt her in her childhood, it had done nothing to aid her development. For in spite of their eccentricity they were commonplace people after all, indolent as only Russians know how to be, given to endless procrastination, enough to drive an energetic nature crazy. Though always more or less on the move, it took them weeks before they fairly got under way, and this interregnum, when the furniture would be stowed away, the domestic arrangements upset, the boxes ready packed in the passage, used to drive Marie, who hated interruptions, half frantic.

The journey through Italy, with the sight of its churches, palaces, museums, and picture-galleries, was a new and thrilling [xv] interest to Mile. Bashkirtseff, a born artist down to her pretty pink finger tips; her fashion of seeing, admiring, criticising the most celebrated masterpieces of painting and sculpture is refreshingly amusing and original. She takes nothing on trust. She is undaunted by names that have gathered authority from the suffrages of centuries. What most closely resembles nature, she says, pleases her most. The ideality of Raphael, the magic of Titian, the haunting mystery of Leonardo, leave her unawed, and she utters strange heresies — which give the relish of a sauce piquante to her crude and youthful criticisms, containing always a considerable admixture of truth, as when she is speaking of the card-board painting of Raphael, and the magnificent but stupid Venuses of Titian — enough to make the orthodox in art shudder! Why should this young observer take it for granted that those old masters are so impeccable? She comes of a new race and looks at things from a new point of view. She has little reverence, less awe, no gratitude for the sacred debt we owe to the past. She, a child of fifteen, pronounces judgment on the masters of Venice and Florence. But how difficult it is to steer clear between abject conformity and parrot-like repetition of long accepted verdicts on the one hand, and on the other an originality of view which leaves you entirely at the mercy of your personal idiosyncrasy. However eccentric at times, Marie Bashkirtseff ‘s opinions have, at any rate, always the merit of being home-made.

It may be said she was a born impressionist. Long before she had ever heard of the existence of such a school she belonged to it. It was in the air; and being as sensitive as a thermometer she answered to all the changes in the intellectual atmosphere of her time. Nothing is more singular than the way in which she reflects the political events of the day. She seems intuitively to feel the public pulse, and without any personal object in view to change as it changes as naturally as a chameleon alters its colour according to the objects by which it happens to be [xvi] surrounded. In this respect she would have made a capital leader writer. Indeed, among her innumerable ambitions was that of writing for one of the French papers, and one of the finest pieces of style in her Journal is unquestionably the glowing description of Gambetta’s funeral. At such times the excessive egotism which fills the universe with her personality is obliterated, and her enthusiasm and eloquence carry everything before them. For she has the power of letting her soul be swept out by the wave of some great national emotion; only to recoil back upon herself, as, for example, when she confesses to wondering whether some caller had given her credit for the tears she had shed over Gambetta’s death.

Everything finally resolves itself into a subject for observation, reflection, and analysis.

But to take up the biographical thread again. The stay at Rome in 1876 marks a fresh period in Marie Bashkirtseff’s development. The city of the Caesars and the Popes, with its historic greatness fallen into decay, yet so glorious still, acts upon her like strong wine. “Its beauties and ruins intoxicate me,” she exclaims in her enthusiasm, and with her wonted impulse to become that which she admires, she wants to be “Caesar, Augustus, Marcus Aurelius, Nero, Caracalla, the Devil, the Pope!” Her brain and blood were on fire, her beauty increased in charm, her intellect in subtlety; with her unique power of assimilation she became a portion of that fierce, dreamy, enchanted Roman life. Wonders of art and history, rides on the Corso, balls and masquerades of the Carnival, with youth and love and beauty sweetening the whole — what more can mortal want? A romance with all the accessories complete! Pietro A____ , the dark-eyed young Roman “with a moustache of twenty-three,” was in turn passionate and playful, soft yet daring, with that finished grace and perfection of manner which come natural to the thoroughbred Italian. This nephew of a powerful Cardinal, possibly of a future Pope, was not a suitor to be wholly scorned nor yet to be heartily accepted. He had no great career in view, was still [xvii] dependent on his family for support, and skimmed along the surface of life like the gay butterfly he was. But this fichu fils de prêtre, as she mockingly calls him in her diary, had a potent charm for the ambitious young Russian — a charm which made her loth to let him go, and long for his return. Was it first love or the fancy of an hour, the caprice of a coquette or an experiment in love-making? Perhaps a little of all these, for with so complex a nature, analytical at once and emotional, it was difficult for her to be quite genuine and simple. But since her own account of the matter is a mass of contradictions, how shall any outsider determine whether her heart had been really touched, or merely the “feminine envelope” which was so excessively feminine. There is the description of that wild ride in the Campagna; of those long evening hours when sitting apart from the rest she listened to Pietro’s passionate declarations of love with his burning eyes thrilling her pulses; of that secret midnight interview at the foot of the staircase in the gloomy old palace, with its inane repetitions of “I love you”’ and the bewildering glances and heart throbs; and that kiss on the mouth which, for months and years afterwards, stung her with intolerable shame whenever she remembered it — all these glowing moments seem to rise up with an assurance that she loved her Roman lover for the time being — probably the happiest time of her life. But she never lost herself in her love. Either it was not strong enough, or she was too strong for it Her egotism, her microscopic analysis of her own and her lover’s feelings, her craving ambition, which made her regard marriage as the ladder by which to reach the palaces, pictures, jewels, all the glittering accidents of fortune for which she thirsted — all these counter currents of her nature acted as opposing influences, and diminished her capability for love. For the rest, some years later, she declares love to be an impossibility to her. “Would you really know the truth?” she cries. “Well, then, I am neither painter, sculptor, nor musician, [xviii] neither woman, daughter nor friend! Everything finally resolves itself into a subject for observation, reflection, and analysis. A look, a voice, a face, a joy, a pain, are immediately weighed, examined, noted and classified, and when I have noted it down I am content.” What is this but saying in other words that she is a poet, a painter, a psychologist, and that her brain, in its enormous activity, draws to itself and consumes all the other elements of her being. In her poem, “A Musical Instrument,” Mrs. Browning has expressed something of the same kind by that metaphor of the reed that has had the pith taken out of it, and henceforth gives forth the sweetest sounds at Pan’s bidding, but will never grow again “as a reed with the reeds in the river.”

Everything was tending to concentrate Marie Bashkirtseff’s thoughts on art. It opened to her a refuge in which her self-tormenting soul might find some peace by giving her an outlet for her restless energy. The great match she had sometimes planned with cool worldliness, seemed beyond her reach. Even the journey to Russia, whither Marie went to bring about some sort of reconciliation between her parents, with a view to her own settlement in life, had no result so far. She boasted many devoted slaves, admirers who gratified her insatiable vanity, but most of them, man-like, after having been attracted by her personal fascination dropped off frightened at her vast superiority to themselves. As for her, she would none of them, and one after another of her parents’ matrimonial arrangements fell to the ground. After the brilliant experiences of Nice, Rome, and Paris, provincial life in Russia, when the first novelty had worn off, proved rather flat.

The manners and customs of her countrymen repelled and shocked her in many ways. During her second visit in 1882 to Gavronzi, her father’s country house, two young princes, Victor and Basil, came to see them, evidently appearing on the scene as desirable suitors for Marie’s hand. They [xix] were apparently men of the world, the eldest having an air of distinction, and she had taken a good deal of pains with her own appearance in honour of these young nobles. But what were her sensations when she saw the youngest, the Prince Basil, kicking and digging his spurs into his coachman, who had got drunk according to his wont. No wonder she had a creepy feeling down her spine, and was eager to get away from a country whose people crawl in the dust before such men as these.

Art, always the delight, now became the master-passion of Marie Bashkirtseff, and in 1877 she finally determined to devote her life to it About this time she speaks quaintly enough of the old age of her youth; indeed, living as she did so much faster than ordinary mortals, years were hardly the measure of her age. At any rate, she had already outlived many illusions, cast many things behind her, and knew a good deal of what was going on behind the scenes of life. When she entered Julian’s life-school in Paris, where women, though working in a separate atelier, enjoyed precisely the same advantages as the male art students, she registered a solemn vow: “In the name of the Father and the Son, and the Holy Ghost! I have decided to live in Paris, where I shall study, and in the summer go for recreation to the springs. All my fancies are over, and I feel that the time has come for me to take a step. This is no ephemeral decision like so many others, but a final one; and may the Divine protection be with me!” From a life of change and excitement she now passed to the monotony of real hard work. Each morning at nine she was driven to the studio, going home for the twelve o’clock déjeuner, and returning at one for the afternoon. Her astonishing capacity became a wonder to her masters, who would hardly believe that she had had no previous instruction save the regulation school-girl lessons. Her daily progress is minutely recorded in the Journal with constant changes from elation to despondency. She flung [xx] her whole ardent soul into her work with a fierce determination to conquer the technique of her art, and she had every encouragement to persevere, Julian assuring her one day that her draughtsmanship, considering the shortness of time she had been at work, was actually phenomenal. “Take your drawing,” he said, “take it to any of our first artists, I don’t care whom, and ask him how much time is required to draw from the life like that, and no one — do you hear? — no one will believe it possible to have done it in less than a year; and then tell them that after a month or six weeks you draw from the life with that solidity and power.” After eleven months of study the medal was awarded to Mile. Bashkirtseff by Robert Fleury, Bouguereau, Lefevre, Boulanger, and Cot.

Little by little a great change came over her. She grew more serious, concentrated, and profound. A deeper sympathy stirred within her, a keener perception of the many-coloured humanity around. Her bosom-thoughts were not entirely given to the favourites of fortune, she dwelt occasionally on the outcast by the wayside, on the child-waif housed by the street. True, there was a picturesqueness in dirt and rags which she looked for in vain in the fine mansions and spacious avenues of the Champs-Elysées. But the attraction which these sights possessed was deeper rooted than that. It had its origin in a vivid feeling for the tragic contrasts in man’s lot, and later on might have turned her into a painter, with so profound a grip of reality as to invest the everyday life around with the impressiveness of history. There are passages in her Journal, describing the drama of the street, that are like flashes of inspiration. She reads subtle meanings in the looks, the attitudes, the movements of passers-by. and suggestions of human tragedies in many a race caught sight of in the crowd. Mothers with children in arms, boulevardiers smoking in a cafe, the sight of a pretty girl leaning on a counter selling funeral wreaths with a smile on her lips — these things strike her as the very [xxi] stuff to be turned to the artist’s use, and as fit for the brush as when

—“Some great painter dips

His pencil in the gloom of earthquake and eclipse.”

Indeed, it was a keen delight to Marie Bashkirtseff to escape from her elegant world and go prowling through the Quartier Latin, looking for rare old editions, for plaster casts, for skulls. The music shops, the bookstalls along the Seine, the busy throng of students and workpeople, appealed to her artistic sense, and the contradictory creature even took to chiding her luck, in that she had been born to wealth and luxury. This change of mood was partly due to her rivalry with one of her fellow-students, the most gifted of them — a young Swiss lady called Breslau, who, living plainly and laboriously in true art-student fashion, appeared to her rival more fortunate, in being wholly free from worldly distractions. This promising artist, who had begun some years earlier than Marie, was a thorn in her side, for she continually tested herself by the attainments of the former, making careful calculations as to whether, at such and such a date, her work had been equal or superior, or the reverse, of what she was capable of producing herself. Indeed, one of the worst traits of Mile. Bashkirtseff ‘s character is her abiding jealousy, nay envy — though she repudiates the word — of her fellow-student, whose success robbed her of sleep, whose failure gave her a thrill of relief. She seems to have been incapable of that glow of enthusiasm which in youth at least cements the comradeship of followers of the same art. But in extenuation we may say with Blake —

“The poison of the honey bee

Is the artist’s jealousy.”

In speaking of Marie Bashkirtseff as a born impressionist, I referred to her instinct and temperament even more than to her bias as an artist. For she belongs to the naturalist rather than the impressionist school. To reproduce the real [xxii] as faithfully as may be, to catch hold of the life of to-day, the common life of the streets, vagabonds, gamins, working people, strollers, convicts, and what not — this is her great object. She asks to be face to face with actual facts, instead of dealing with figments of the fancy; to present the “living life” through the medium of colour as she so triumphantly managed to convey it through that of words. What she aims at above all therefore is expression — truth of expression. Not beauty, not invention, not —

“The light that never was on sea or land.”

That light is precisely what she scorns. No, no, give her the light as it slants across a dingy wall in a narrow Parisian back street, on which a boy has scrawled a gallows; or the rain dully boating on a tattered umbrella. That is nature, the nature we see most commonly about us, and which we can render with the greatest accuracy of presentment.

For she is an enthusiastic disciple of Zola, the master of a school which has set the ugly in the place of the beautiful, as Milton’s Satan called on evil to be his good. In reading some of the novels, and looking at some of the pictures produced by the latter-day followers of this gospel of the gutter, one would say that nature was one universal chamber of horrors. There is enough and to spare, no doubt, but it would be well to remember sometimes that the sun is still shining in the sky, and man not absolutely a brute. Even in our own day, with our own eyes we have seen the angel in the man; the names of Mazzini, of Gordon, of Damien, have made us sad and glad, and it is as well to remember that they are as much part and parcel of human nature as the drunkard of “L’ Assommoir” and the scoundrel of “L’Immortel.” Yet in justice it must be said that the reading of the former novel called out Marie’s sympathies for the sufferings of the people in a way that nothing else had ever done, the description of their misery making her positively ill, and leaving a permanent mark [xxiii] behind. If she seemed by preference to select ugly subjects for presentation, it must not be forgotten that she went in for rendering what she saw, and that she lived in the Paris of the latter part of the nineteenth century. Had she remained in her native Ukraine it might have been different with her, for she might have found subjects to her hand as full of character as they were of beauty and originality. Indeed, she was intensely sensitive to the beauty of life, as her jubilant admiration of Spain proves very conclusively. A word must be said here about her journey to that country, which was the turning point of her career as an artist. She was a pupil when she went -there, a painter on her return. Formerly she had only seen the drawing and the subject. Now she seemed suddenly to have acquired a new sense, and atmosphere and colour stood revealed. Velasquez took her by storm. His unrivalled technique, his brush-power, the monumental realism of his work, made her raise “herself on tip-toe to catch the secret of his divine truthfulness.” Fashion may have had something to do with this unbounded enthusiasm. For though original in her judgments, Marie Bashkirtseff is the

most impressionable of human beings, and the name of Velasquez was the rallying cry of the naturalists.

Not only Velasquez, however, the entire country stirred her artistic faculties as nothing else had ever done before. The fantastic old churches and palaces born of the marriage of Moorish and Gothic art, the fairy-like gardens full of the murmur of fountains falling between beds of violets; the grace of the black-eyed Spanish women and supple-limbed gipsies in the tortuous streets, turning into pictures with every chance grouping and accident of light and shade — here, indeed, the common stuff of life was food for the painter’s canvas. Pen and pencil became equally inspired, and her descriptions of Spanish life and scenery, of the bull-lights and cigarette makers and convicts, are among the most powerful and picturesque pieces of writing in the Journal. There is an aptness [xxiv] in her phrase, a crisp clearness of outline and vigour of presentment making these passages worthy of a master of style.

The fire of inspiration caught from the genius of Velasquez and Ribera, and the architectural marvels of Toledo and Granada, burned with a steady flame during the short span of life still left to this marvellous girl.

In August, 1882, she painted The Umbrella, remarkable for the striking truth and precision in the delineation of character, the Holbeinlike accuracy of the drawing, the vigour of the pose. It is the picture of a girl of twelve wrapping her old shawl round her as she stands impassive, with wind-blown hair facing the rain under a bent umbrella of Gamp-like dimensions. The expression of the stolid face full of that pathos of mute suffering which occasionally startles one in the looks of animals is a piece of admirable realism. The same vigour and solidity of handling are evinced in Jean et Jacques, exhibited in the Salon of 1883. Two boys, the elder brother holding the reluctant little one by the hand, trudge to school with unwilling steps. Jean, sucking a leaf between his lips as a make-belief cigarette, his cap rakishly on the back of his head, and umbrella tucked under his right arm, has the business-like air of those children of the poor who are left in charge of babies from the time they could toddle. A more ambitious effort in the same line, and a really fine picture, Le Meeting, was begun in April, 1883. The title was a stroke of wit, when applied to half-a-dozen lads discussing the use to which a piece of string is to be applied with the excitement of politicians over a question of state. We know them, these gamins de Paris, these young habitues of the gutter, flocking together like hungry sparrows, picking up their food anyhow, yet managing to grow in a devil-may-care sort of way. Little love, less learning, falls to their share, yet the great city is their schoolmaster, and for aught we know they may hear “sermons in stones,” though not sermons of the orthodox, but rather of the Louise Michel kind. But they [xxv] are not altogether a bad sort. True, that big, thin legged fellow with the fox-like look, laying down the law to the audience, may grow up to brew mischief in the State, but at present the lucky find of a stray nest or length of stick yields trim a throb of satisfaction. A set of ugly, unwashed, badly-clothed ragamuffins. You or I passing them in the street might have looked another way to avoid seeing their dirty rags. Yet how interesting, how full of life and character they are, just a group snatched, out of the busy throng, and still warm and breathing, translated into the language of art. Though grey and sombre in colour this picture is harmonious, nay, even brilliant in tone. It has a real atmosphere, and the figures stand out vigorously from the gloomy background of the street, partly blocked up by a wooden paling. The naturalness of the composition, the admirable truth of the general effect, the vigour of the execution, the sense it gives us of latent force instinctively assimilating and reproducing the pictorial elements of common life, combine to make Le Meeting a memorable performance for a girl of twenty-two who had only started on her artistic career five years previously.

Expression being her forte, as might be expected portraiture is one of Marie Bashkirtseff’s strong points. She has done nothing more successful and admirable than the pastel of her cousin Dina, to be seen in the Luxembourg, as well as Le Meeting. Her portraits of Mme. P. B, her sister-in-law, of Bojidar Karageorgevitch the Servian Prince, and of Mile, de Canrobert, bear the unmistakable stamp of being characteristic likenesses. The latter is particularly noticeable for the ease and freedom in the lines of the figure ; though rough in workmanship there is style in the pose, and in the treatment there seems a suggestion of Mr. Whistler’s manner.

Landscapes with figures also attracted the young artist; and the word-painting of some of her projected works in [xxvi] that line — such as the description of the funeral of a peasant girl in spring, whose coffin is carried to its last resting place through a blossoming apple orchard — is as lovely a piece of writing as we know. She imagines the delicate harmonies of pale pinks, the infantine green of the new leaves and untrodden grass, the delicious blue of the rain-washed April sky, hues that have the soft and soothing effect of a flute heard across the waters of a lake; and amid all that glory of young leaf and blossom the bier of the dead girl, and some rough old country people by the wayside, as gnarled and rugged as the bronzed trunks of the apple-trees.

The two subjects of that kind which she actually did paint are full of charm and suggestiveness. The one is an avenue in autumn, breathing of desolation and decay. There is something almost human in the miserable look of the trees stripped of their sumptuous clothing, and shivering in their bones, so to speak. A dull, deadly mist steals up the path like a shroud which invisible hands are bringing to cover the earth. The ghostly air of abandonment fully gives the sentiment of this phase of nature; and, indeed, landscape painters agree that autumn, with its mists and rich discolourations, is the most pictorial of all the seasons. The other, called Spring, painted at Sevres in April, 1884, was the first of her pictures which found its way to Russia ; and that, too, in a manner most flattering to the artist, for it was bought, early in the year 1888, by the cousin of the Czar, the Grand Duke Constantine Constantinowitch, not only a distinguished connoisseur, but himself something of a painter and poet. It is now in his gallery at the Marble Palace, which contains several works of the highest merit. In this picture Marie Bashkirtseff attempted to express the inmost spirit of spring by line and colour — the rush of sap in the vegetation, the exquisite modulations of green, the little yellow flowers in the grass, the sheen of white and pink blossoms; in short, the mysterious fermentation of revival [xxvii] culminating in the person of a rustic girl half asleep under an apple-tree. She is meant to express that “drowsy numbness” of extreme physical enjoyment which Keats so magically describes in the “Ode to a Nightingale” A frame of mind in which, as the downright painter says, she would easily have succumbed to the first young boor who would see her sitting there.

But we do not realise Marie Bashkirtseff’s astonishing energy, power of work, and devotion to her art, till we have seen the quantity of sketches, designs, and studies from life, which she managed to produce between the ages of seventeen and twenty-four. These have been carefully preserved by the pious love of Mme. Bashkirtseff in the house where her daughter spent the two or three last years of her life in a kind of artistic delirium, laying in a picture, modelling in wet clay, improvising wondrous times, studying Homer, Livy, and Dante, stretching the hours into days by the number of sensations she managed to cram them with.

Well might Marie say that there was nothing wanting to her artist’s happiness in the way she was lodged. She had a whole storey entirely appropriated to herself. The spacious atelier has a splendid light, and a gallery running round it, the whole being crowded from floor to ceiling with her work. There is the first portrait she painted — a woman in a blue dress — of which the most noticeable feature is the treatment of the hands and fair silky hair. The Study of a Fisherman of Nice, browned by the sun, with that rich flesh colour, to which the blue sea acts as a foil, is a powerful bit of character. The Comtesse de Toulouse Reading shows a more delicate feeling for beauty than is usual with her; the action of the long, white fingers passing through the waves of golden hair being masterly in treatment. So is the sketch of a baby at the breast. There is something almost fiercely realistic about it; only a breast and the infant’s face; [xxviii] but the blue-veined temples, the blue-pink tones of the cheeks and unfinished little nose, the energy of the sucking lips, are caught to the life. The head of the convict she painted at Granada shows the influence of the Spanish school. It is a face full of expression, the sinister physiognomy looking out from the canvas with a strange vividness. The same influence is shown in the masterly study of a pair of hands. They reveal a character, and suggest a story — a tragedy, if you will I know not what of ages of pain and endurance is conveyed by those long, bony, corded hands, but they are not easily forgotten. More of a finished work is the picture of a child of nine walking through an avenue with a bottle in one hand and a tin pail in the other. The soft blue of the gown harmonises very happily with the neutral tints of the ground and the trunks of the trees. The naive expression of the child, and the action of the sturdy little feet are admirably true to nature. The general effect is full of poetry of the Wordsworth kind.

But it is impossible here to give a detailed account of the many things of interest contained in this studio. The general impression left on the mind is that Marie Bashkirtseff excels in the vitality of her work. Everything she touches catches life from her fingers. Insignificant in subject, ugly, uninviting it may be, but it lives, and makes you feel that it does. Herein lies her great gift, and one she so highly prized ! But she has other qualities as a painter. She can paint atmosphere so that her figures are well detached from the background, and there is no confusion of objects ; she is noticeable for her effects of delicate gradations of light, and her colour has a subdued sweetness of tone, rather sober for so ardent a nature.

The fine library leading out of the atelier shows what a student and lover of books Marie Bashkirtseff must have been. Valuable editions of the Greek and Roman classics stand in orderly rows along the shelves. The literatures of Italy, [xxix] France, Germany, England, and Russia, are represented by all their chief authors. A striking photograph of Zola, for whom this artist entertained so pronounced an admiration, hangs on the wall opposite the writing table. But these rooms contained what seemed to bring Marie Bashkirtseff in the flesh more vividly before me than the books and the furniture, the statues and pictures, and all the rest of it. Only a cupboard full of little shoes — house-shoes, dress-shoes, ball-shoes — but what a world of pathos was there not in those bits of leather or satin which had shod those small Cinderella-like feet, of which the young girl was almost as vain as of her beautiful hands. For Marie was much occupied with her appearance, fond of dress, and had more than the ordinary share of a woman’s love of attracting admiration. She had a finely developed figure of middle height, hair of a golden red, the brilliant complexion that usually accompanies a tendency to consumption, and a face which, without being regularly handsome, captivated you by the fire and energy of its expression. Photographs could never do her justice, it seems, as the want of colour deprived her of that unrivalled freshness and fairness which constituted her chief beauty. But her real spell lay in the intense vitality which shone out of her deep grey eyes, as it glowed through all her writing and painting. Even the illness which was to carry her off added fuel to the flame, and she might well say — “I am like a candle cut in four and burning at all ends.” For consumption, whose first symptoms had already been discovered by the doctor of some German watering-place when she was only sixteen years old, was unfortunately suffered to spread and undermine her constitution. She would not, or could not, believe in the reality of the skeleton in her cupboard, though a thousand fictitious ones were always driving her distracted. The dark shadow so early cast across her path threw the high lights of life into sharper relief, and no premonitory warning sufficed to make [xxx] her realise the imperative need of taking care of herself. If she did so at all, it was only by fits and starts under the stress of an attack of laryngitis or pleurisy. She was the despair of her physicians. Potain, the great chest doctor, who pronounced her the most extraordinary and undisciplined of all patients, refused at one time to have anything more to do with her, for she coquetted with Death as much as with one of her lovers, dallying and luring him on at whiles, but instinctively drawing back when his advances became too marked. Sometimes, however, when she realises his frosty breath so close upon her, she shudders instinctively, crying out in anguish — “To die; great God to die! Without leaving anything behind me! To die, like a dog, like a hundred thousand women whose names are scarcely engraved upon their tombstones!” But this was not all. The trouble that fretted her above all other trials was a growing deafness, which interposed a barrier between her and the outside world. This infirmity seems, in some cases, to accompany the pulmonary complaint, and by robbing human intercourse of its zest, destroyed her hopes of a brilliant social career. On that account it was more horrible to her than the idea of death itself — partly because the misery of it was a dull, dreary, monotonous one: whereas to die young was still to find “an intoxication in death itself.”

But before the end came her life burned with a clearer, more concentrated flame than ever before. She herself is taken by surprise at the increasing acuteness of her sensations. Time seemed too limited to reproduce the beauty of the universe. In fact, painting was but one of the forms through which her prodigious sensitiveness found expression. She wished to be a sculptor too, so as to express the beauty of the human form in its completest manifestation. Music was another vent for her intense personality. When she sat down to the piano in the moonlight of May to play Beethoven or Chopin, all other pleasures became tame by comparison. [xxxi] Then would she glide into strange new harmonies, such as may sound through an opium-eater’s dream. “No one,” she exclaims, “no one it seems to me, loves everything as much as I do.” This passage in the Journal has the same ring of exaltation as Shelley’s “Ode to Delight,” when he sings his love for

“The fresh earth in new leaves drest,

And the starry night ;

Autumn evening, and the morn,

When the golden mists are born.”

The year 1884 now dawned — the year which brought Mile. Bashkirtseff a striking artistic success; the closest friendship with Bastien-Lepage, the painter she admired above all others of her generation; and the end of all things. Le Meeting, the picture already spoken of, was exhibited in the Salon of ’84, and attracted public attention. It had press notices in the leading papers, and was reproduced in many of the illustrated ones of France, Germany, and Russia. Dealers and picture-buyers began to look up the rising artist; society papers described her personal appearance, speaking of her as one of the most beautiful girls of Russia. When she went out she came in contact with the intellectual elite of France, and was noticed as a person of distinction, and a young, charming, elegant woman, all in one. Ah, at last, her dreams were translated into reality! She not only felt herself a force, she was recognised as such. The fact gave a new impetus to her whole nature; the greatest triumph of all being Bastien-Lepage’s assurance that no woman had ever achieved so much at so early an age.

Marie’s admiration for the painter of Pas Méche, Jeanne d’Arc, Le Soir au Village, has a suspicious flavour of love about it. At any rate it is the strongest, sweetest, most impassioned feeling of her existence, lending a tender halo to its last phase. Is there anywhere in fiction, indeed, a chapter more pathetic, more thrilling than the [xxxii] intimacy of these two impressionist painters as we see it growing and deepening in the closing scenes of the Journal? At first the presence of “the great, the only, the unique Bastien” used to make Marie so nervous that she grew awkward and tongue-tied when they met. She even goes the length of protesting that there is a natural antagonism between them, because he acts as a check upon her and she taxes herself with exaggeration for this excessive enthusiasm only due to a master-genius like Wagner. But these doubts and hesitations passed away on Bastien-Lepage’s return from Algiers, whither he had gone for health’s sake. On his return to Paris in the summer of the year ’84, Marie and Bastien met nearly every day, either in the latter’s sick room or else in the Bois de Boulogne.

These were days full of solemn sweetness, when the Moi-Spectateur sometimes left off looking through the microscope, and Bastien, whose very name had some time haunted her like the refrain of a song, was always so delighted to see her, so disappointed when she stayed away. The two families met almost daily; there was a constant interchange of delicate attentions. The goat which supplied Marie Bashkirtseff with milk provided Lepage likewise; pride, shyness, reserve vanished, and they became simple and trustful like two children clinging to each other when left alone in the dark. She tells of foolish little details, enough to make one weep, indeed, she almost dreads Bastien’s recovery, which will put a stop to this intimacy.

Alas! there was no fear of that, as became all too soon apparent to her. The year was on the wane and they were on the wane with it. Day by day the Journal initiates us into the mystery of the closing act of life till we seem to witness the change, the gradual relaxation of all earthly bonds and affections. On coming away from the bedside of Bastien, who was sinking fast, Marie often felt quite detached from the earth already. The thirst, “the fever called [xxxiii] living” seemed to be stilled, a painless indifference, the most unusual sensation with her, left Marie resigned to everything. She already felt herself a shadow drifting with Bastien into the shadow land. Indeed, she was very ill herself — so ill, that with all her determination she found herself unable to paint. She had begun a picture of La Rue, the subject being a seat on the Boulevard des Batignolles, with its customary occupants. Everything was ready to her hand for beginning this work. A photograph of the corner of the street had been taken, she had made a preliminary sketch, the canvas was placed on the easel ; in short, as she pathetically says, “All is ready. It is only I who am missing.”

It was on the 12th of October that, growing from bad to worse, Marie was kept in-doors. On the 16th, exhausted with fever, she was only able to move from the easy-chair to the sofa. Bastien, too weak to walk, was carried to her room on the shoulders of his devoted brother Émile. Propped up on cushions the two dying artists lay near each other, finding a supreme consolation m being together to the last. Marie Bashkirtseff, not forgetful of appearances even then, wore a tea-gown of ivory plush with a cloud of soft lace of every shade of white. The artist’s grey eyes, “eyes which had beheld Joan of Arc,” as she says, dilated with pleasure as he looked at her. She was still beautiful, and his passion for art, possibly his passion for the woman, awoke the longing to fix her image before she had faded away. As he looked his last at the ruddy gold of the hair done up in a simple knot, still so bright above the ardent face with its pale velvety complexion, the deep-set eyes glowing with a sombre light, the light of a soul on fire — no wonder the painter should exclaim impulsively: “Oh, if I could only paint!”

That is all. The picture of the year is finished! The Journal breaks off abruptly on the 20th of October, 1884, and eleven days afterwards, on the 31st of the month, shortly before completing her twenty-fourth year, Marie Bashkirtseff [xxxiv] had ceased to be, and was followed shortly afterwards by Bastien-Lepage, so that in their death they were not divided. She lies buried in the cemetery at Passy, where a monument has been erected to her memory, with some verses by M. Theuriet engraved over its portal.

Could Marie Bashkirtseff have known what a sensation she has produced since her untimely end, even her thirst for renown might have been appeased. Could she have known that her chief picture was bought by the State within a year of her death, and now hangs in the Luxembourg along with the masterpieces of modern French art; could she have known that her Journal is an enthusiasm to the few, a curiosity to the many, and is taking rank among the autobiographies the world will not willingly let die; could she have known of the essay which the spell of her personality has drawn from the grand old humanitarian leader of England — could she have known all this, it might have compensated her for much in her life, and would have spared her that haunting dread of perishing with nothing to show that she had been — “rien, rien, rien!”

MATHILDE BLIND.