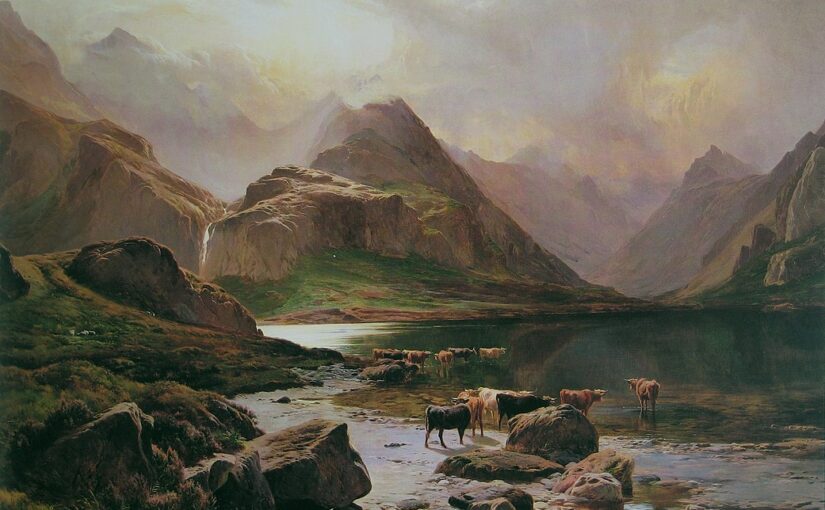

[NOTE: Mathilde Blind wrote three letters to Richard Garnett during her August-September 1873 tour of the Isle of Skye and the Northwestern Highlands of Scotland; below are annotated excerpts from each of them. These letters, along with those written about her visits to the islands of Staffa and Iona, provide important contexts for three of her subsequent poems either set in or incorporating Scotland (“The Prophecy of St. Oran,” The Heather on Fire: A Tale of the Highland Clearances, and “The Ascent of Man“). The image above is a painting of Loch Coruisk on the Isle of Skye, by Sidney Richard Percy (1874; in the Public Domain)]

Excerpts from 23 August letter (Add. MS 61927 ff. 199-200):

Cuidrach

W. Portree

Isle of Skye

Aug. 23rd 73

My dear friend,

This is a strange place is it not to write from but solitary, silent and sad as it is there is something of a congruity between it and me; some subtle unison, which makes me feel less lonely here than I often and often feel in the crowded London streets.

A bare-looking stone farm-house, endless reaches of short, spare grass, and the waters of Loch Snizort 1 winding in and out between low sterile rocks, this is the whole scene. I now may add to it today a grey sky, a faint mist, the plaintive cry of the quail heard now and then or the lowing of a cow breaking a silence so deep that it seems almost to become horrible. 2

It is true about two miles from here you get a very nice view, and that too of a unique character. Looking down black precipitous rocks you come in sight of the pretty little bay . . . with a few houses (great rarities here) and a little kirk sprinkled along the shore; beyond that lies a glassy sea on which the island of Harris, with its clear cut aerial hills, rests like an exhalation a breath of wind might dissolve. These sea-girt Hebrides, have an oceanic depth of colour, a delicate purity of outline, an evanescent bloom which partakes more of the appearance of some white Avilion 3 than of our common and substantial earth. . . .

Yours most sincerely

Mathilde Blind 4

Excerpts from Blind’s second letter to Garnett about her visit to Skye (Add. MS 61927 ff. 207-09):

Cuidrach

W. Portree

Isle of Skye

Sept 6th 73

My dear friend,

I was very pleased to have your letter which bore no signs of having been written when you felt fagged with a heavy correspondence. I am fagged too this evening, but it is with a long walk I took along a steep rocky coastline from which I had a magnificent view of some of the Hebrides. The hills of these Islands have certainly a more Alpine character than anything one can see out of Switzerland. In my long solitary walk I sometimes came upon whole flocks of swarthy or snow white sea-birds who startled by my steps took sudden flight and winged their way across the dark blue . . . . These and a few sheep nibbling the scanty grass were the only things breathing in this absolute solitude where on could almost hear the “tingling silentness.” 5

. . .

I saw a good deal of Skye (which by the by signifies in Gaelic the Winged Isle) in this drive. The character of the interior is extremely monotonous and anything more miserable than the hovels in which the inhabitants live it would be difficult to imagine. They are merely a few stones put roughly upon each other and thatched with heather and straw. They have often neither windows nor chimneys and the thick peat smoke issues by the door. Sitting by the wayside I saw some old hags which outside of a fairy tale one would scarcely have thought possible. The children are not so bad-looking but indescribably dirty.

Many thanks for your kind offer of securing me some books if I wish it but I think these I have will suffice for the present. It is true I have only the Edda, the Nibelungenlied, the Morte D’Arthur and Shelley with me but there is much matter to be got from them. . . . 6

Excerpts from Blind’s third letter to Garnett about her visit to Skye (Add. MS 61927 ff. ff. 218-219):

Oban.

Argyleshire

Sept. 25th /1873

My dear friend,

I have been almost constantly on the move since I wrote you last. From Portree I went to Loch Maree, the grandest of the Highland Lakes, I believe, and but little known as yet. The road from the head of the Loch to a place called Talladale is exceedingly fine. I especially enjoyed the luxuriant deer forests which gently sloped down from the side of the tremendous mountains, whose bare glistening summits receded far backwards gleaming here and there through grey rolling vapour. The mountains here have a very straight aspect, owing to their peculiar geological formation, some glimmering like silver above the fir woods, while on the opposite shore the great black mass of Ben Slioch rises precipitously from the water’s edge. The contrast between these wild blasted rocks, unrelieved by a vestige of colour, save for the sparkles of a cascade here and thee, and the green and purple shore richly cushioned with heather and fern and flushed with the clustering berries of the rowan trees is very beautiful.

I was storm-stayed for nearly three days at a lovely hotel there. And such a storm! Walking along the banks of the Loch I saw what looked like some dark nebulous host rushing from the further end of the lake and advancing with a weird moaning sound which made the trees shiver through all their branches till the pale leaves fell pell mell to the earth. And then the tempest of hail, sleet and rain burst right over my head. So heavily did it beat on the Loch that the water splashed up as if stones were falling into it and the surface where it hailed looked one white seething mass several feet in height, not stationary, however, but traveling onwards with incredible rapidity. Now and then the lightning flashed through the gloom of cloud and forest and the thunder was exacerbated from one hundred heaths. Rainbows followed in the wake of the hurricane, and it was astonishing to see the hurrying storm now descending on the further summits while the barren mountain side which had been invisible but an instant before was now clothed in the most delicate hues which like a zephyr, wafted by an imperceptible breeze, hovered on from hill to hill. – These strange appalling gusts were renewed many times during that and the following day although with each fresh fit the storm seemed to lose somewhat of his first strength. At last on the morning of the third day the sun shone forth, the vapours lolled languidly about Ben Slioch whose dim peaks soared untrammeled above them, and I found it possible at last to be rowed in a boat to some of the small islands with which the centre of this Loch is studded. One of these called Eilean Baree [presumably Eilean Sùbhainn] is thickly wooded and covered with ferns and rushes of every description. Half hidden amid all this greenery are grey tombstones, with strange half-effaced crosses still faintly discernible here and there. Not far from this spot full of an indescribable pathos is a deep dark well where folk of yore used to go in order to be healed of every kind of disease. An old fir-tree stands above it and its bark is pierced with various coins which the people used to offer up to the spirit of the place (or perhaps the nymph of the well). I could not learn from my guide for whom these offerings were destined. – I might tell you much more but want to post this ere night so must cut short further accounts of what I have seen.

- [A sea loch in the northwest of the Isle of Skye between the Waternish and Trotternish peninsulas]

- In his September 13 letter to Blind, Garnett noted: “I don’t think, by the way, that you will find any quails in Skye; the birds are probably plovers or curlews.” (Add. MS 61927 f. 213)

- The legendary island of Arthurian legend.

- In his 29 August reply to this letter, Garnett wrote: “You describe the scenery of Skye very beautifully.You ought to be writing poetry, or at least imbibing influences conducive thereunto. I gather that the scenery has the kind of peculiarly Celtic aspect which Mr. Arnold finds in Celtic literature, and distinguishes by the name of magic. A sort of wistful melancholy tenderness as if nature there were more deeply inspired with a soul than elsewhere. I suppose it is an aerial effect, depending chiefly on the combination of atmospherical persuasion extremely. If the Cader mountains are less sublime than the Snowdonian, they are more romantic. One great beauty is the incipient music of waters in the valleys and winds upon the hills” (Add. MS 61927 f. 202).

- The quotation is from the

first stanza of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem “Alastor; or, The Spirit of

Solitude”:

EARTH, Ocean, Air, belovèd brotherhood!

If our great Mother has imbued my soul

With aught of natural piety to feel

Your love, and recompense the boon with mine;

If dewy morn, and odorous noon, and even,

With sunset and its gorgeous ministers,

And solemn midnight’s tingling silentness;

If Autumn’s hollow sighs in the sere wood,

And Winter robing with pure snow and crowns

Of starry ice the gray grass and bare boughs;

If Spring’s voluptuous pantings when she breathes

Her first sweet kisses,–have been dear to me;

If no bright bird, insect, or gentle beast

I consciously have injured, but still loved

And cherished these my kindred; then forgive

This boast, belovèd brethren, and withdraw

No portion of your wonted favor now! - In his 13 September response to this letter, Garnett wrote: “I am truly glad to receive your letter, and thank you much for your beautiful descriptions of the solitary scenery where you are at present. There must be something very attractive in this perfect repose combined with freedom—the absence of the sensation of being hemmed in by something of which one can rarely get rid in any part of England. It should seem, with fine weather, the very scenery for autumn, which is beginning to steal upon us here, making itself perceptible in morning mists, sharp air, and a tenderness of light in the faintly-pencilled skies. The last few days have been perfect September, and therefore very pleasant ones” (Add. MS 61927, f. 211-12).