[NOTE: the letters quoted here between Mathilde Blind and Richard Garnett come from the British Library’s manuscript collection, titled Correspondence and Papers, 1866–1896, catalogued as Additional Manuscripts, volume 61927. All photographs on this page were taken on 24 June 2016 by James Diedrick]

On 26 September 1873 Mathilde Blind wrote to her friend and long-time correspondent Richard Garnett (who was then Assistant Librarian in the British Museum) from Oban on the west coast of Scotland:

Oban

Argyleshire

Sept. 26th/ 1873

My dear friend,

I cannot leave this place without telling you of my trip to Staffa and Iona, which is certainly one of the most interesting excursions to be made in the Highlands. The weather was very favourable which was lucky for me as the vessel during the greater part of the time is out on the open Atlantic, or has to take her way round wild precipitous capes whose base is lashed by the white angry surf.

She first describes the Isle of Mull:

On leaving Oban one first enters Loch Linnhe, a beautiful sheet of water bounded to the left by the lofty shores of Mull, while the famous Morran range extends far to the right and seems to terminate in the misty bulk of Ben Cruachan. Low wooded heights slope down to the water’s edge and are crowned by many a ruin and cattle, or white farm-house giving an exquisite finish to the landscape.

Then Blind describes leaving Mull and heading toward the uninhabited island of Staffa: “as the Steamer recedes from the black, iron-bound coast the blue ocean heaves around looking more cast for the Treshinish Islands, strange, isolated rocks half submerged in the waste of waters.”

Next comes her description of Staffa and Fingal’s Cave:

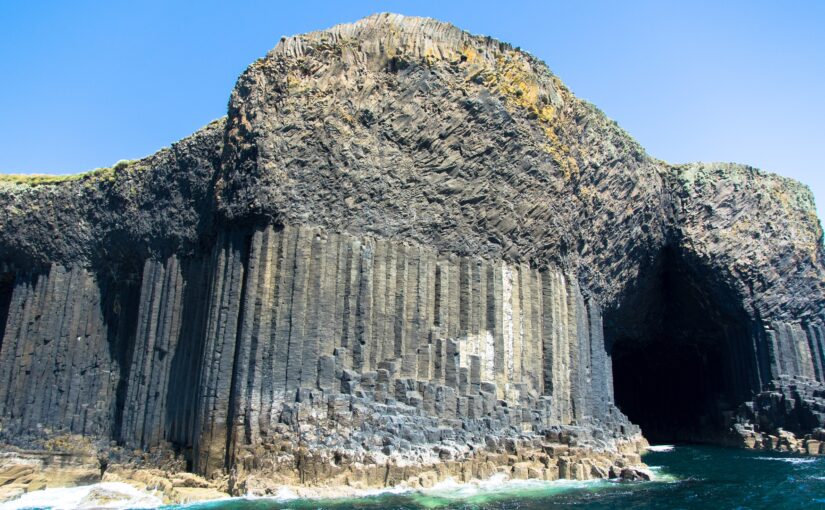

Staffa too, seen at a distance, looks only such another bare-worn mass of stone. But drawing near to it you are filled with astonishment at the marvelous regularity of its structure. At some distance from the shore we were let down into a life-boat and rowed to the island. As you draw near to it the water becomes perfectly limpid, and in its clear green depths, far branching, faint-hued sea plants swayed silently to and fro. It was a magical sight. – But I was recalled to reality on landing at Staffa over whose rugged shore covered with moist and slippery stones one has to pick one’s way to Fingal’s Cave. . . . You gradually ascend from the shore till you stand on a rocky ledge when again you have to descend an awfully steep path at the foot of which you see the seething surf. I despair of describing to you the cave itself. You hang as it were midway between what looks like the nave of a natural Cathedral paved by the wandering wave. Columns disposed in wonderful symmetry support the lofty arch, and the muffled thunder of the tide resounding from the profoundest recesses of the cavern is a music more sublime than the peal of the finest organ.—What must it be could one see this astonishing work of Nature on a moonlight night or a wintery Storm (Blind ALS to Garnett, 26 September 1873, Add. MS 61927, ff. 224-28).

Blind’s expression of “astonishment” at the “marvelous regularity of its structure” here refers to the fact that Staffa was formed entirely from hexagonally jointed basalt columns within a Paleocene lava flow. Fingal’s Cave itself was by this time well known to Blind and others because of Felix Mendelsohn’s “The Hebrides Overture,” composed in 1830 and popularly known as “Fingal’s Cave.” The popularity of Mendelsohn’s overture made the cave a popular tourist destination in Blind’s lifetime, though earlier visitors—including Sir Walter Scott, Wordsworth, and Keats—were drawn there by James Macpherson’s Fingal, an Ancient Epic Poem in Six Books (1761), which is the source of the cave’s name.

Looking out from Fingal's Cave

Richard Garnett replied to Blind’s descriptions in a 30 September letter:

The first piece of poetry I ever learned—or at least taught myself to repeat was the description of Staffa in Scott’s Lord of the Isles, of which of course I did not at the time understand one syllable, but was attracted by the melody of the versification: I still remember with pleasure

That wondrous dome

Where, as to shame the temples decried

By skill of earthly architect

Nature herself, it seemed would raise

A minister to her makers’ praise.

Not for a meaner use ascend

Her columns, or her arches bend;

Nor of a theme less solemn tells

The mighty surge that ebbs and swells,

Had still, between each awful pause,

From the high vault an answer draws

In varied time, prolongs and high

That mocks the organ’s melody.

Nor doth its entrance front in vain

To old Iona’s holy fane

That Nature’s self might seem to say

Well hast thou done, frail child of clay!

By humble powers that starkly shine

Tasked high and hard, but witness mine!

I think this should settle the question whether Scott was a poet. Like you, he was struck with the cathedral-like character of the interior, and the aspect of the cavern towards Iona (Garnett ALS to Blind, 30 September 1873, Add. MS 61927, ff. 231-33).

The second part of Blind’s letter, describing her visit to Iona, can be read here.