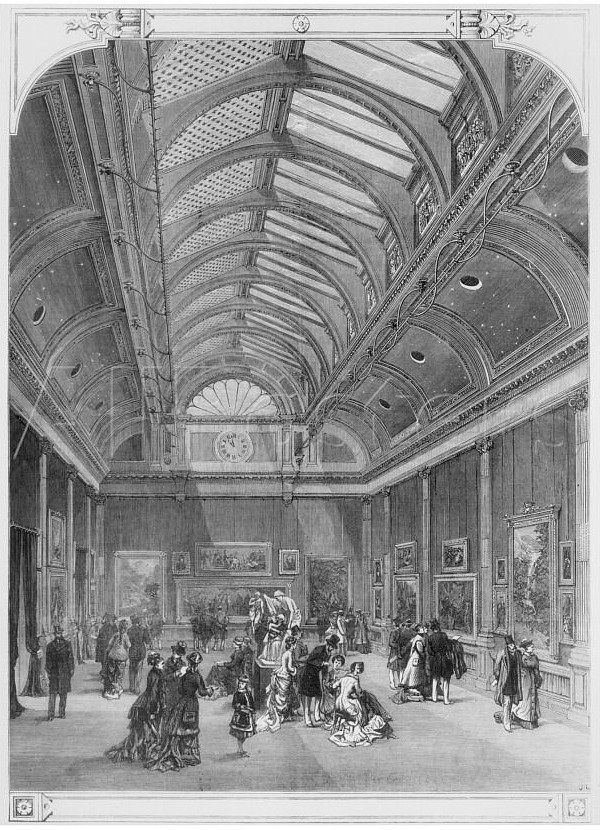

The Art Weekly, 12 July 1890: 165-67. Image above: Interior of the Grosvenor Gallery – West Gallery, published in The Illustrated London News, 5 May 1877

[NOTE: This is one of four essays Blind contributed to the Art Weekly, co-edited at the time by her friend and fellow poet Rosamund Marriott Watson. All four demonstrate Blind’s knowledge of contemporary art and artists as well as the critical independence she maintained even when reviewing those artists she knew well (as shown in her essay “Mr. Ford Madox Brown’s Pictures at Dowdeswell’s). This is an omnibus review of portraits exhibited in 1890 at the New English Art Club, The Grosvenor, The New Gallery, and the Royal Academy of Arts,]

It is many years since the first banner inscribed “Down with the Portraits” was raised on high, but even now it is almost annually flung to the gale of controversy. The public, moreover, are its upholders—the unknowing many whose shillings enable the painter to display his work, to “give it bold advertisement.”

The public cares nothing for a portrait, unless it is of some celebrity, of whom they may assume a knowledge by crying confidently, “Oh, that’s so-and-so of course: how like”; or of some dear personal friend, when they can relieve their over-burdened minds by abusing both the presentment and the original.

Why then are they so persistently supplied with an article which they not only do not demand, but would rather not have? The reason is obvious and remedy there is none, for the roots of the nuisance (from the public point of view, of course) run right down to two fundamental principles of human nature—Interest and Vanity.

The Interest is the painter’s. Those who “please to live must live to please,” and it is manifestly better to depict a subject, however uninteresting, with the assurance of pocketing the golden guineas when it is done, than to lavish unappreciated beauties upon a stolid populace who leave the artist to starvation.

The Vanity is the “paintees,” if I may coin the word. What is the use of providing that one’s features shall be handed down to an indifferent [166] posterity by ______ or _____ and paying smartly for the same, unless our friends and acquaintance writhe with envy at the fact? And so the portrait musts be exhibited, and the public groan.

Both parties to the transaction may possibly exclaim that this view off the matter is unfair, but let the facts speak. The members of the New English Art Club [founded in London in 1885 as an alternate venue to the Royal Academy] it cannot be denied are staunch supporters of Art for its own sake, and the pot-boiling portrait finds small favour in their eyes. But one-fifteenth of their exhibits were portraits at all—Mr. Greiffenhagen taking first place with his charming “Miss Lilly Hanbury”—and of those, Mr. Walter Sickert’s “Miss Fancourt” was rather a colour study after his master’s famous manner, his “Mr. Bradlaugh” a light effect, while the portraits of Mr. Wilson Steer and Mr. Sickert were the result of a pleasing mutual admiration.

From the Water-Colour Galleries we learn the same lesson. In the Royal Society’s room Mr. Carl Haag’s curiously lighted and disagreeably coloured “Worshipful Master” is the sole instance, while at the Institute the absence of this phase of Art production is almost equally conspicuous.

Clearly enough the portrait patron cares not for water-colour; it has a cheap effect,–“Only a water-colour” says the carping friend—and is less likely to be seen on the walls of the less frequented galleries. It is at the New Gallery with its one-sixth of portraits, the Grosvenor with its seventh, the Academy with its ninth, exclusive of miniatures and sculpture that the proud owner likes to behold his counterfeit presentment on the walls.

To merely refer by name and number to each of the three hundred odd portraits suspended this year in the three last mentioned places would fill the pages of this paper, and much work excellent or otherwise must necessarily be passed over in silence that the best or worst may receive justice.

Taking them in order as they present less to notice—as the child does the easiest lesson first—few at the Grosvenor rise above mediocrity. The best is Mr. Shannon’s “Miss Kathleen Pelly” (15), an excellent picture of a charming child. In 36, Mr. Orchardson immortalizes himself for the painter’s Valhalla at the Uffizzi in a work in which clothes, face, and background are merged in the curious golden light which always characterizes his productions. It would be invidious to specify the worst portrait of the year, but Mr. B.S. Marks’ “Sir Philip Magny” (42) goes very near it, and Sir John Millais’ “Master Ranken” (60) is not far off. Mr. Stuart Wortley is scarcely happy as a portrait painter, and “The Lady Hastings” (62) is perhaps the weakest of four weak efforts. The most pretentious portrait is that of the members of “The Court of Criminal Appeal” (150) by Sir Arthur Clay, in which much solid work is somewhat marred by the textureless flesh, which is so shiny that it seems to suggest that the judges of the land are as a body most highly polished gentlemen. Mr. Jacomb Hood has failed to master the foreshortening in his seated figure of Mrs. Cavendish-Bentlinck (153), so that an otherwise clever portrait appears unnaturally short in the body and large in the head. The Hon. John Collier sends the strongest male portrait in this gallery—that of “Richard Henry Williams, Esq.” (203), while Miss Edith Ellison’s “Stella Peskett” is delicate and truthful. Mr. Heywood Hardy has painted the “Ladies Hilda and Alice Dundas” in two little companion pictures, but as might have been expected has been more successful with the horses than the riders. Mr. Henry Muhrman asserts that 162 is a portrait and he ought to know, but it would have been wiser if he had announced also what it was meant to be a portrait of.

The New Gallery [121 Regent Street, London; served as an art gallery from 1888 to 1910] is in advance of the Grosvenor in the matter of portraits, both as to quantity and quality, owing not a little to the contributions of Professor Herkomer, whose four portraits (Nos. 28, 33, 39, and 43) in the first room are alike admirable. In the same room Miss Blanche Jenkins has a portrait of “Miss Ruby Davis” (9), which, though rather weak in handling, is very bright and childlike. Close by hangs “A Portrait” (20) by Mr. La Thangue—a very clever rendering of attitude and expression by artificial light. Mr. Edwin Ward depicts Mrs. Strode Jackson (66) with considerable command of the slap-dash style, but is seen at his best in 377, “Peter,” a little picture relegated to a dark corner in the balcony. Mr. Furze’s “Mrs. Abrahams” (74) is rather a study of a lost profile than a portrait, but taken at that is skilful. Mr. Sargent’s ruthless reproduction of Mrs. Comyns Carr is brilliant, though coarse. “Mrs. Whitelaw” (99), by Mr. Shannon, with its subtle arrangement of greys and greens, contrasts startlingly with his gloomy and uninteresting “Sir Alfred Lyall” (64). Mr. Philip Burne Jones seems to be in a fair way to be spoiled by success, for of his five portraits not one can serve to advance his reputation. Mr. Richmond contributes one of the many Episcopal portraits this year, and shrouds “The Bishop of Bath and Wells” (107) in a uniform and depressing slatey greyness. Mr. Hartley’s portrait of “Mr. Fennessy” is a sound piece of work; and Mrs. Swynnerton, in spite of sloppy painting, has infused much life and spirit into her rendering of two boys (192). “Mr. John Burns,” argumentative and business-like, may well be called a “striking” likeness by the Hon. John Collier. “Miss Cooper” (227) fares well at the hands of Mr. Shannon, which is more than may be said of the aristocratic musicians in Mr. Clifford’s lifeless production. The balcony contains the customary collection off miscellaneous work, of which Mr. E.R. Hughes’ red chalk portrait of “Dorothy Parker” (268), Mr. Bogle’s black and white child (289), Mr. Rudolph Lehmann’s drawings, especially that of Cardinal Manning and the well-known one of Mrs. Browning, are worth remarking.

In the Academy [the Royal Academy of Art], the portrait patron absolutely revels, and Messrs. Sant, Richmond and Wells provide a goodly supply of the usual material, while Mr. Fildes, and his portraits of “Mrs. Agnew” (303) and of “A Lady” (467), reaches the ideal of rich material and expensive upholstery to which the patron aspires. Mr. Ouless, as always, takes the highest place, his “Angus Holden, Esq.”, (74), “Sir Donald Smith” (80), and “The Bishop of Chichester” (197) being the best of five, all of which are excellent. Mr. Richmond’s “Bishop of Durham” is broader and simpler than is the wont of his work, but “The Countess of Yarborough” (449) is more textureless and overloaded with detail than ever.

It is remarkable how unfortunate in their attempts at portraiture are those Academicians whose specialty lies otherwhere. Mr. Long, Mr. Tadema, Mr. Pettie, Mr. Orchardson, and Mr. Calderon, all yield in merit to many an outsider, Mr. Herkomer alone keeping well to the fore with his powerful “Major Burke” (318) and “Miss Vlasto” (502). Mr. Arthur Cope has some capital work, of which “Mrs. Robert Walpole” (3) and “Edward Sanders, Esq.” (260) are the best. Mr. Solomon’s “Mrs. Mosenthal” is another brilliant portrait, but Mr. Carter’s “Mayor of Oxford” is a sad example of the effect of Mr. Ouless’ method in less powerful hands. If Sir John Millais has ever painted a [167] worse portrait than that at the Grosvenor, it is that of Mr. Gladstone and his grandson (361). It is not worthwhile deciding too nicely which has the uncoveted distinction. Mr. Sargent’s “Portrait of a Lady” is dashed off with a careless ease which, carried to excess, renders “Mrs. K” (652) crude and flat. Mr. Jacomb-Hood takes a stride forward with his firmly-modelled portrait of “Miss Shaw-Lefevre” (436). Mr. Cecil Burns shows a pleasing portrait of a child (591), but it is hung too high to be fairly judged. Mr. Colin Hunter’s sea-faring brush staggers woefully in portraiture, if “Master Gordon Ness” (694) is a fair sample; and Mr. Blake Wirgman’s “Sir James Hannen,” and Mr. Ernest Breun’s powerful “Cold Steel” (1114) should put him to the blush.

There are a number of miniatures, a form of art which seems to be growing again in public favour, but neither they nor the busts come within my province; and of the few water-colours, none call for special mention.

All things considered, Mr. Ouless’ “Bishop of Chichester” is, beyond doubt, the best portrait of the year, while the worst—but I am not sufficiently well read in the law of libel to proceed.

M. B.