[NOTE: Blind wrote this biographical “Memoir” of Shelley for her 1872 one-volume edition of a selection of Shelley’s poems, published as volume 1207 of what grew to over 5,000 volumes in Bernhard Tauchnitz’s “Collection of British Authors.” Though she wrote to Richard Garnett on 31 August 1872 that “it is a great pity I can’t have 2 volumes to do the selection in . . . as with one it is barely possible to make a proper book of it,” she also recognized that by undertaking this project she could enhance her status as a Shelley authority. Her memoir is notable among other things for its original, feminist claim that the character of Cythna in The Revolt of Islam “is a unique creation. . . . a creature self-contained, not as satellite moving around man as the centre of her thoughts and actions, but rather in unison with him revolving round the nucleus of a common aim” (xxi).]

[NOTE: Blind wrote this biographical “Memoir” of Shelley for her 1872 one-volume edition of a selection of Shelley’s poems, published as volume 1207 of what grew to over 5,000 volumes in Bernhard Tauchnitz’s “Collection of British Authors.” Though she wrote to Richard Garnett on 31 August 1872 that “it is a great pity I can’t have 2 volumes to do the selection in . . . as with one it is barely possible to make a proper book of it,” she also recognized that by undertaking this project she could enhance her status as a Shelley authority. Her memoir is notable among other things for its original, feminist claim that the character of Cythna in The Revolt of Islam “is a unique creation. . . . a creature self-contained, not as satellite moving around man as the centre of her thoughts and actions, but rather in unison with him revolving round the nucleus of a common aim” (xxi).]

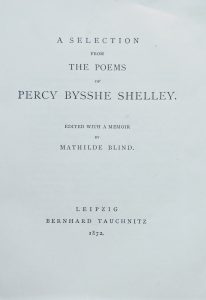

“MEMOIR OF SHELLEY.” In A Selection from the Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Edited, with a Memoir by Mathilde Blind. Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1872. VI-XXXVIII.

AUTHORITIES

Percy Bysshe Shelley. Letters from Abroad, Translations, and Fragments, Edited by Mrs. SHELLEY. A new Edition. London, 1854.

Mrs. Shelley, Notices in her collected edition of the Poems.

Lady Shelley, Shelley Memorials. London, 1859.

William Michael Rossetti, The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. A revised Text with Notes and a Memoir. 2 vols. London, 1870. Contains the first methodical narrative of the entire life of the poet.

Thomas Jefferson Hogg, The Life of Shelley. This reaches only to the beginning of the year 1814. 2 vols. London, 1858.

E.J. Trelawny, Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron. London, 1858.

Thomas Medwin, The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley. 2 vols. London, 1847. The Shelley Papers and the conversations with Lord Byron. 1824 and 1833.

Thomas Love Peacock, 3 articles published in Fraser’s Magazine in 1858 and 1860.

Richard Garnett, Relics of Shelley, London, 1862.

The Autobiography of Leigh Hunt. A new Edition. London, 1860.

MEMOIR OF SHELLEY.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, the greatest idealistic poet of England, was born on the 4th of August 1792 at Field Place, near Horsham, Sussex. Is it fanciful to surmise that the tremendous revolutionary storm then, with fierce yet salutary throes, convulsing society touched as with an electric influence this new-born soul? At any rate it is an indisputable fact that the passion for a radical reform of the world as regards a juster distribution of human happiness, which was the motive power of that colossal upheaval we term the French Revolution, formed no less the ruling impulse of the divine genius who to quote his own words was in very truth a

“Nerve o’er which did creep

The else unfelt oppressions of the earth.”

Meanwhile with the strange discrepancy of events this spiritual child of the Revolution, is by the irony of fate born heir to one Mr. Timothy Shelley, a country gentleman and respectable Whig, able to trace back his pedigree to the times of Edward I. We can hardly wonder that so strange a phenomenon as this wild-eyed poet with his humanitarian enthusiasm startled, perplexed and utterly bewildered the good Sir Timothy, (for such he became on the death of his father) nay doubt if even we should wonder where it clearly proved that the worthy man contemplated sending his son, when ill with brain fever, to a private mad-house. To a beef-eating, port-drinking British Whig and M. P. of that time a passionate fervor for abstract principles probably did appear as a most irrefragable symptom of insanity.

The future Anti-christian received in baptism the names of Percy Bysshe. The later name was that of his grandfather, a man who, to judge from his success in life, [VII] possessed considerable practical ability. Originally without means he, through his own exertions and two successive marriages with heiresses, amassed a large fortune and left son one of the opulent heirs of the kingdom. Of Shelley’s mother, who exercised but little influence on her son, nothing further is to be said than that she appears to have been a kind sensible woman. The family besides the poet consisted of four sisters and one brother. As “the child is father to the man” it is of interest to know that Shelley from the days of his infancy delighted in tales of ghosts and fiends, and that at a somewhat later period when at home for the holidays he used to hold his sisters spell-bound by his vivid description of alchemists, wizards, and a “Great Tortoise” with which he peopled the house and garden.

The boy, after having attended day-school for some years, was sent to Sion House School, Brentford. We can easily conceive that an imaginative delicately reared lad underwent a good deal of acute suffering from a stern Scotch master Dr. Greenlaw, and a set of rude unmannerly boys.

Not much better fared it with Shelley when at the age of fifteen he was sent to Eton. His dauntless championship of the weak against the strong may be said fairly to have been commenced there. He rose up in arms against the existing state of things by his violent opposition to the system of fagging then flourishing vigorously at all public schools. No amount of bullying or persecution proved successful in in enforcing his own submission to the obnoxious practice. If he thus put himself in antagonism to his schoolfellows, he was on an equally hostile footing with the ruling powers of the establishment. Dr. Keate the head-master was a strict disciplinarian who did not “spare the rod.” The consequence was that Shelley, who by gentle treatment and calm reasoning might have been led as a child, was instigated to unflinching resistance. He was on much the same terms with all the other masters: Dr. Lind,1 a physician, [VIII]being the only influential person at Eton to whom he looked up. Between this amiable man and Shelley one of the rare and beautiful intimacies was formed, than which none more sacred exist, that of a wise and gentle old man cherishing the warmth and enthusiasm of his young friend, and striving to communicate to him to him the accumulated thought and knowledge of the years. What a deep impression this intercourse left on Shelley’s mind is shown by the fact that he has twice reproduced the image of his venerable master and friend; once in the Revolt of Islam, where he is the prototype of the old sage who liberates Laon, and once in the exquisite fragment of Prince Athanase, where he figures as Zonoras.

Shelley’s taste for chemistry was greatly stimulated if not first awakened by Dr. Lind, and this study engrossed a great portion of his time at Eton. The fact of its being forbidden fruit may possibly have added zest to the pursuit. Certain is it that mischief on mischief was brewed by this chemical infatuation. We hear of a tree set on fire on the common by lighting with a burning glass; of a tutor violently hurled against the wall by a highly charged electrical machine, and other like exploits productive to this martyr of science of unpleasantly tangible results in the shape of floggings.

Shelley, although neglectful of school attendance, was yet in his own way zealous in his literary studies; he evinced a marked facility in making Latin verses, and translated Pliny’s Natural History.2 It may also be worthy of notice [IX] that even at this early period he went among his school-fellows by the title of “Shelley the Atheist.” This nickname however was used by Etonians not in the common acceptation of the word, but implied that the youth thus styled had distinguished himself by unusual pluck in his defiance of the powers that be, viz. the school authorities.

We will now accompany Shelley to Oxford, where he was entered at University College in the autumn of 1810. Between his transit from Eton to Alma Mater some time elapsed, which was spent at Field Place and the occasion was diligently improved by Shelley to sprout forthwith into a lover and an author. The object of his first passion was his cousin Harriet Grove, said to have resembled the poet in features; the first products of the author, two extravagant romances possessed of no merit, are best, even as regards their titles, consigned to oblivion. A volume of poems entitled “Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire” not only deserved the same fate but has actually incurred it, for not a single copy is known to exist.

Settled at Oxford, Shelley, with characteristic vehemence, plunged into the studies most attractive to him. Mr. Jefferson Hogg in his delightfully picturesque although somewhat overcharged “Life of Shelley” has brought before us the warm almost breathing image of the poet whose inseparable companion he became. It is clear from this narrative that in those days Shelley possessed a glow and buoyancy of spirits quenched by the tragic events of his later life.

Not uninstructive for a full comprehension of the poet’s individuality will it be to follow him into privacy as it were and note those tricks of manner and trifling habits which are often surer indications of character than long descriptions or important actions would be. Let us then watch him, as on a frosty winter’s afternoon, he sallies forth with his friend to enjoy his favorite recreation, a long country ramble. See how he strides across country, the tall active frame somewhat lessened by a slight stoop, the hands ever and anon rapidly passed through the eccentric quantity of dark [x] brown curly hair, the wide eyes with a fixed far-away look, as if they saw over and beyond all visible objects. Thus impetuously pushing on, he yet all the while with half-reverted head argues with his friend,–(for to argue on all questions was his dominant passion) expatiating probably in glowing terms on the Platonic theory of knowledge being but a reminiscence of an antenatal state. In the course of their walk he swings to and fro a pair of dueling pistols, and his companions assures use he had perpetual reason to apprehend that, as a trifling episode in the grand and heroic work of drilling a hole through the back of a card, he would shoot himself or me, or both of us.—But a new object now serves to attract his attention. They have sighted a pond. Shelley, riveted to its side, hastily seizes on any letter of paper he has about him, dexterously fashions tiny paper boats then with rapt attention, as though his fate depended thereon, he watches the fortune of the fairy fleet as it battles with miniature waves and mimic storms. The hungry Hogg, who does not share his friend’s childlike tastes, stamps impatiently up and down the frozen soil, and at last by sheer force drags oblivious Shelley out of the icy night-air in to fireside and supper. The eager disputant has on a sudden become unaccountably silent. What has become of him? When lo and behold the marvelous boy stretched on the rug in deep sleep, his little round head exposed to the blazing fire; but seemingly as impervious to its heat as a cat. The awakening process is accomplished with as startling a rapidity as the going to sleep; and to dash instantaneously into a vehement argument or launch into the recital of verses protracted with inexhaustible enthusiasm till late into the night was the frequent practice of the student.

These were the pleasures of our poet. As regards study we have it on the authority of Hogg that he was a whole University himself in respect of the stimulus and incitement which his example afforded. Sixteen hours out of the twenty-four were frequently spent reading. Locke, Hume, [XI] the French Encyclopædists,3 together with Plato, as yet chiefly known for Dacier’s translation, formed some of the works most eagerly perused. Absorbed by speculations on religious and philosophical subjects, and under the impression that by honest argument many sound conclusions might be arrived at, he was in the habit of writing anonymously to various person of literary celebrity. He likewise drew up a little syllabus entitled The Necessity of Atheism, which he circulated enclosed in letters and wherein he professed to have come across the pamphlet and to be unable to refute its arguments. This pamphlet became known to the authorities, who, suspecting Shelley to be the author, summoned him to admit or deny the charge, and on his refusing to do either instantly expelled him (March 25, 1811). Hogg who ventured to protest shared the same fate. It is doubtful whether Shelley was, even at this period, a confirmed materialist. To judge from Queen Mab, which embodies the poet’s thought at this time, a strong admixture of Platonic idealism tinctured his views even then, nevertheless to all practical intent and purposes he was an Atheist.

We may still add that Shelley’s residence at the University had been marked throughout by the singular purity of his morals, the gentleness of his manners, and an abstemiousness in diet that verged on the ascetic. He already inclined to vegetarianism, which from March 1812 he resolutely adopted.

In a certain sense it may be said that Shelley now found himself cast adrift on the Metropolis. His father refused to receive him, and his mother and sister she could only see by stealth; neither was any allowance made him at that time, [XII] and he subsisted mainly on the pocket-money supplied to him by the latter. To one exquisitely sensitive as Shelley, although buoyed up by the proud consciousness of martyrdom, the situation was painful enough. He was separated from his best friend Hogg, and the courtship which had been carried on for some time with the lady already mentioned was now finally broken off. To judge from expressions in letters the poet suffered severely from this defection of the girl he loved. In this frame of mind it was but natural that any new object which could arouse an affectionate interest would possess double attraction for the desolate young heart. This was not long in making its appearance on the scene of action in the shape of a beautiful girl “with a complexion brilliant in pink and white—hair quite like a poet’s dream and Bysshe’s peculiar admiration.” This was Harriet Westbrook, daughter of a retired hotel-keeper in easy circumstances, and who, placed in the same boarding-school as Shelley’s sisters, used to be dispatched by them with pecuniary help to their brother. Thus an intimacy commenced, and Shelley as was his wont carried on a correspondence with her, in which he dilated his on his moral and religious convictions. During a sojourn in Wales he received a letter from the girl in which she complained of her father’s petty tyranny and expressed herself as ready to “throw herself on his protection.” The result of all this was that Shelley eloped with her in September 1811 to Edinburgh, where they were speedily married.

This was unquestionably an unfortunate step, the result of which might be easily foreseen. But we will not anticipate. Shelley and his wife for the next three years led a very nomadic existence. We find the young couple at York, where they were joined by Harriet’s elder sister Eliza and intended to spend the winter with Hogg who pursued his law studies in that city;–at the Lakes, where Shelley made the acquaintance of Southey;–at Dublin (1812) where he was engrossed by efforts to further Catholic Emancipation;–at Lynmouth in Devonshire circulating printed bills for [XIII] the enlightenment of the people, which contained a Declaration of Rights similar to those of the French Revolution;–at Tanyrallt in Carnarvonshire whence he precipitately retreated hurried off by an actual or imaginary attempt as assassination. As the would be murderer was never traced, and no adequate reason appears to exist for the attempt to be made, it seems probable that the incident was a hallucination produced by the unstrung condition of Shelley’s nerves and the effects of laudanum which to mitigate acute spasmodic pains he was then in the habit of taking. After another erratic flitting to Ireland the wanderers at last settled in London, where Shelley’s daughter Ianthe was born in 1813.

Shelley now printed but did not publish Queen Mab; and the audacious poem created a certain sensation; it was considered by Byron, to whom the author sent a copy, as a work of great power. We share in this opinion. The principal charm lies doubtless in the exuberance of its boundless hope, in its strong vital sympathy with the past sufferings and faith in a happier future of Humanity; it is the first irrepressible burst of a “High spirit winged Heart” through its chrysalis; and as such its fresh spontaneity would redeem verse more manifestly imperfect than that of Queen Mab.

A domestic crisis was now approaching. Shelley’s theory, as may be gathered from notes to Queen Mab, was that “From the abolition of marriage, the fit and natural arrangement of sexual connexion would result. I by no means assert,” he writes, “that the intercourse would be promiscuous: on the contrary it appears from the relations of parent to child, that this union is generally of long duration, and marked above all others with generosity and self-devotion.” If in spite of these tenets he married first Harriet and afterwards Mary Godwin it was chiefly on account as he writes of “the disproportionate sacrifice which the female is called upon to make.” We may easily surmise that such being the theoretical conclusion, in the event of radical incompatibility of [XIV] nature such as that existing between Shelley and his first wife, there would be no inherent obstacle to prevent the severing of the tie.4 According to this view if Harriet acceded to the separation there was not the slightest dereliction of duty. The question then is whether Harriet was equally willing with himself to dissolve their connection, and as to this we possess no positive evidence. At the same time it must be admitted that whatever the outward causes of dissention may have been, under no circumstances whatever is it probable that the union could have been productive, to Shelley at least, of anything but intolerable anguish. There is reason for inferring that he struggled for a time with the growing misery of his lot and this stanza written only in thought, as he says in a heart-rending letter addressed to his friend Hogg, will give some insight into the state of his feelings:

“Thy dewy looks sink into my breast

Thy gentle words stir poison there;

Thou hast disturbed the only rest

That was the portion of despair!

Subdued to Duty’s hard control,

I could have borne my wayward lot:

The chains that bind this ruined soul

Had cankered then—but crushed it not.”

This state of things however could not last. Shelley left Harriet in May 1814, and afterwards came to some sort of understanding with her. His relations with her seem to have continued on a certain friendly footing, but it is [XV] impossible to decide whether on Harriet’s part this was owing to meek acquiescence in the inevitable, or whether she was herself not averse to the step. However this may be, she returned to her father, and soon gave birth to a son, Charles Bysshe; Shelley making such arrangements for her comfort as his circumstances allowed.

“Fair and fair-haired, pale indeed, and with a piercing look” such was the impression Mary Godwin at the age of sixteen, made on Hogg. She was the daughter of the author of Political Justice and of Mary Wollstonecraft, whose powerfully written Rights of Woman had won for her a wide celebrity. The child of such “glorious parents” had imbibed from their united teachings many opinions, which, while directly at variance with those held by the world at large, closely resembled Shelley’s. To her the poet violently in love declared his passion, as they met one day in St. Pancras Churchyard, by her mother’s grave. Mary, who had learned to regard marriage as a ceremony, which could in no wise sanctify the union of two beings truly loving each other, unhesitatingly joined her fate to that of her lover’s, and the two, accompanied by Miss Clairmont (a daughter of the second Mrs. Godwin by her previous marriage) started on the 28th of July 1814 in an open boat for Calais. The three fugitives (for such they were in a sense as the wrathful Mrs. Godwin went up after them, in pursuit of her daughter be it remarked) after tossing about on the Channel all night sighted land and the rising sun at the same time.

They then, after some days’ stay at Paris, chiefly in order to procure the necessary funds to proceed on their travels, set off with the intention of walking through France. Whether haunted by shadowy recollections of the travels of “The Holy family in Egypt” or not, they likewise procured for themselves the services of one of the mild and long-eared species and another Mary graced the back of another ass. But it was soon alas! discovered that the poor little donkey instead of carrying stood more in need of being carried itself, and had in time to be exchanged for a mule, [XVI] which not acquitting itself with much more credit, was in its turn replaced by a voiture. In the course of their wanderings they passed through the country which had been the immediate seat of war, and the sight of the burnt villages, the impoverished inhabitants, and the devastated fields, left an indelible impression on Shelley’s mind, which gave double force to his description of such scenes in the Revolt of Islam. Impressions of a more inspiring kind awaited them in Switzerland, whence however, they were quickly driven by pecuniary difficulties. They returned to England by way of the Reuss and the Rhine, the river-navigation enchanting Shelley, who has reproduced its magical effects in Alastor and the Witch of Atlas.

The pecuniary embarrassments already adverted to had about this time reached their climax. The poet had never been free from something of this kind from his expulsion from Oxford, although shortly afterwards, his father had been induced to make him an allowance of £200 per annum; he was so lavishly generous, however, that he continually gave away the better part of his income before he was even possessed of it. To give only one instance of his disposition in this respect, Shelley, a few years later than the time of which we are now writing, made his friend Leigh Hunt, with money raised by an effort, a present of fourteen hundred pounds, to extricate him from debt. The above mentioned allowance had been discontinued on Shelley’s leaving England with Mary, and the bare means of subsistence were often raised with difficulty. It should be mentioned that at one time he had rejected with indignation £2000 a year, with the sole condition of the estate being entailed on his eldest son, or in default his younger brother.

The death of Sir Bysshe in January 1815 materially improved the poet’s prospects; his father finding it prudent to make him, as he was the next heir to the state and might have encumbered it with debts, and allowance of £1000 a year. Shelley and Mary now settled at Bishopgate, where the former diligently pursued his Greek studies. Here, in [XVII] comparative tranquility, the magnificent woodland of Windsor Great Park serving as study, Alastor was written. This beautiful poem, pervaded by a

“deep autumnal tone

Sweet though in sadness”

is evidently the product of a revulsion the feelings of Shelley had undergone since their first fiery outburst had fallen so flat on an unresponsive world. Notwithstanding its exquisite charm and greater perfection of form it must be admitted that this poem partakes less of the essential Shelleyan quality than Queen Mab.

In the summer of 1816 Shelley with Mary and Miss Clairmont settled at Mont Alègre on the lake of Geneva: Byron, who occupied the Villa Diodati being their next neighbour. In these scenes hallowed by the genius of another “world-worn heart” that of the author of Nouvelle Héloise, (which Shelley now read for the first time with enthusiastic admiration) the two poets felt strongly attracted towards each other, and the greater part of each day they spent together in boating on the Lake. On one of these excursions they were overtaken by a sudden squall, which placed their lives in imminent peril. Shelley, who could never learn to swim, writes in allusion to this: “I felt in this near prospect of death a mixture of sensations, among which terror entered but subordinately. My feelings would have been less painful, had I been alone; but I knew that my companion would have attempted to save me, and I was overcome with humiliation, when I thought that his life might have been risked to save mine.”

In the evenings the whole party, consisting besides the above mentioned Dr. Polidori, Byron’s secretary and at one time of Lewis a then well-known author, frequently assembled, when the recital of wild unearthly tales would form the chief topic of interest. “After tea 12 o’clock, really began to talk ghostly” writes Dr. Polidori. On one of these occasions Shelley worked himself up to such a pitch of excitement that he [XVIII] rushed out of the room and was found by those who followed him in a trance of horror. The remarkable production of Frankenstein then begun and Mary owed its origin to these weird story-tellings at the witching hour of night.

The uninterrupted intercourse with so transcendent a mind as that of Shelley’s left its mark on Byron. We can trace the spiritualizing influence of the author of Adonais and Epipsychidion in much that is loftiest in the speculations of the third Canto of Childe Harold and Manfred; speculations we do not find in any of the noble poet’s earlier works. What was the latter’s opinion of our poet may be gathered amongst others from the following expressions: “You should have known Shelley to feel how much I must regret him. He was the most gentle, the most amiable and least worldly-minded person I ever met; full of delicacy, disinterested beyond all other men, and possessing a degree of genius joined to simplicity as rare as it is admirable. He had formed to himself a beau idéal of all that is fine, high-minded and noble, and he acted up to this ideal even to the very letter.”

By September 1816 we find the Shelleys again in England and on the point of settling at Marlow in Buckinghamshire, when they were struck with grief and horror by the news of Harriet’s suicide. There is good cause for believing that this tragic occurrence had no direct connection with any act of Shelley’s; but was brought about by new relations into which the unfortunate Harriet had entered. Still we believe it can hardly be denied, that indirectly, if only in the disintegrating influence he had exercised on her views of life in general, he must in a certain sense have conduced to this lamentable result. This, this it is which constitutes the tragic pathos of Shelley’s short life, that one whose every heart-beat from earliest youth had vibrated with an unquenchable love of his kind, a burning zeal for promoting the general happiness, should in his impetuous course carry along with him and shatter the life of a fellow-creature; preparing so sad a fate for himself and another by reaching [XIX] out after a nobler morality than that in common practice. Truly may Leigh Hunt remark: “Let the conventional sowers of their wild oats, with myriads of unhappy women behind them, rise up in judgment against him!”

Another affliction with crushing force soon befell the poet. He was deprived of his children. On the death of Harriet, Shelley naturally claimed Ianthe and Bysshe, and, marvelous to relate, the law intervened. The facts were as follows: Mr. Westbrook refused to give up the children, and instituted against Shelley a suit in Chancery, to prevent his obtaining possession of them. It was stated in the bill then filed, “that the father, since his marriage had written and published work, in which he blasphemously denied the truth of the Christian religion, and denied the existence of a God . . . . . . and that he intended, if he could get hold of the persons of his children to educate them as he thought proper.” The suit was not long protracted, being decided against Shelley on the 17th of March 1817 Lord Eldon giving his judgment to the effect that as “the father’s conduct, which I cannot but consider as highly immoral, has been established in proof, and established as the effect of those principles” he could not think himself therefore justified in delivering his children to their father’s care. In consequence of this decision the infants were placed under the guardianship of Mr. and Miss Westbrook and their education entrusted, oh irony of circumstances! to a clergyman of the Church of England, £200 being deducted from Shelley’s allowance by his father for their maintenance.

“No words can express the anguish he felt when his elder children were torn from him,” says Mrs. Shelley, and again later when the “two gentle babes” he had by her lay buried in Italian cemeteries, she adds his words, “I envy death the body far less than the oppressors the minds of those whom they have torn from me.”

Let us however return from the contemplation of these sorrowful subjects, which affected Shelley for life, and follow him to his retreat at Marlow, were, with Mary, whom he [XX] married in December 1816, for a beloved companion, and his two children, he now passed his days divided between the composition of the Revolt of Islam and the active exertions for the relief of the poor in the neighbourhood. He was deeply shocked at the sufferings of the lace-makers and bestirred himself to ameliorate their condition. He had walked an hospital in London in 1815 chiefly in the hope of being useful to the destitute and now carried out these benevolent intentions. He caught a serious attack of ophthalmia while thus visiting the sick.

About the same time the acquaintance with Leigh Hunt ripened into a warm friendship, and he would often pass several days under his roof at Hampstead. At his house he likewise made the acquaintance of Horatio Smith and Keats. Shelley’s daily life at Marlow is thus described by Leigh Hunt: “He rose early in the morning, walked and read before breakfast, took that meal sparingly, wrote and studied the greater part of the morning, walked and read again, dined on vegetables (for he took neither meat nor wine), converse with his friends to whom his house was ever open, again walked out, and usually finished with reading to his wife till ten o’clock. His book was generally Plato, or Homer, or one of the Greek tragedians, or the Bible, in which last he took a great though peculiar, and often admiring interest.”

The Revolt of Islam being now finished he thus addresses Mary in the dedication:

“So now my summer-task is ended, Mary,

And I return to thee, mine own heart’s home;

As to his Queen some victor Knight of Faëry,

Earning bright spoils for her enchanted dome.

Nor thou disdain that, ere my fame become

A star among the stars of mortal night

(If it indeed may cleave its natal gloom),

Its doubtful promise thus I would unite

With thy belovèd name, thou child of love and light.”

[XXI] This first great poem with its magical charm of inwoven rhythm was made by Shelley the vehicle of the loftiest conceptions of self-devotion, endurance and heroism. But the most witching spell of his genius he cast round the loves of Laon and Cythna. Nothing more divinely sweet probably exists in the whole range of poetry than the description in Canto VI. of their meeting after years of struggles, endeavours and unimaginable woes. It is as if from the very inmost sources of sources of emotion welled forth from an inexhaustible stream of love, so pure, intense and delicately subtle that these wonderful verses may fitly be termed the very incarnation of passion in words. Nothing is more characteristic of Shelley than his constant endeavour to exalt the relations subsisting between man and woman, and in none of his poems is this endeavour so manifest, as in the one we are now discussing.

Through the whole of this mighty liberative chaunt of The Revolt there runs like a golden thread the yearning sympathy with that half of human kind, which although the weaker, is yet burdened with a double weight of oppression, and he cries:

“Can man be free if woman be a slave?”

Cythna herself is a unique creation. She embodies the poet’s idea of pure and lofty womanhood; of a female redeemer walking forth through a great city rousing women “from their cold, careless, willing slavery;” of a creature self-contained, not as satellite moving around man as the centre of her thoughts and actions, but rather in unison with him revolving round the nucleus of a common aim. Yet withal there is nothing cold, hard or abstract about her, she steals on the imagination with the soft glory of sunset and dwells there for ever as a “form more real than living man.”

With these few inadequate words we must take leave of the Revolt of Islam or Laon and Cythna as the title originally stood, and without pausing to analyse its brilliant qualities [XXII] of sound and description return to the fact of the poet’s actual existence.

He was again on the point of becoming a wanderer. For, partly impelled by the distressing events above mentioned, partly by ill-health and an inborn restlessness, he once again on the 11th of March 1818, quitted England with his family, and was destined never to return. This time the goal was Italy, where they stayed in succession at Milan, Pisa, Leghorn, the Baths of Lucca, Venice, Este, Rome, Naples, and back again to Rome whither they returned in March 1819.

The sad and terrible vicissitudes which we have recorded as chequering Shelley’s life had now in a great measure come to an end. His remaining years flowed on with a smoother current, their progress being chiefly marked by the series of astonishing poems, which with rapidity bordering on the miraculous, were now in succession the products of his pen. To take a brief survey of these therefore, glancing at the same time at the surroundings which constantly shifting exercised an influence quasi atmospheric on his imagination, must now form the leading object of these pages.

Rosalind and Helen, a narrative poem, does not strictly speaking belong to this period, having already been commenced in England and being now at the instance of Mrs. Shelley completed. A good deal of the author’s personal experience, such as Rosalind’s deprivation of her children, the obloquy cast by Helen on account of her connection with Lionel, has been introduced into this poem, which is of a more domestic character than is usually to be met with in Shelley.

Shelley’s sojourn in Venice, where he met Lord Byron, who was delighted at seeing him again, was productive of Julian and Maddalo, one of the most captivating and intrinsically original of our poet’s productions. With marvelous success the tone of the familiar conversation of persons of genius and refinement is here given back, in fact the conversation of Byron and Shelley. Of this poem it may also [XXIII] be said that with the exception of the closing act of the Cenci it is the only instance of true human pathos to be found in Shelley, this being an affection of the mind only to be produced by dwelling on the simplest and most generic of emotions, and therefore apt to be a plant of rare growth where the imaginative reason prevailed as was the case here.

Prometheus Unbound was begun at the same place as Julian and Maddalo, I Cappucini, Lord Byron’s villa, at Este placed by him at the disposal of the Shelleys. The bulk of the poem, however, was written at Rome and that chiefly during the delicious spring of 1819 amid the mountainous ruins of the Baths of Caracalla. In letters addressed to friends in England is a minute description of this characteristic study, and on account of its suavity as well as for being a specimen of Shelley’s epistolary style we quote it.

“The Thermæ of Caracalla consist of six enormous chambers, above 200 feet in height, and each enclosing a vast space like that of a field. There are in addition, a number of towers and labyrinthine recesses, hidden and woven over by the wild growth of weeds and ivy. Never was any desolation more sublime and lovely. The perpendicular wall of ruin is cloven into steep ravines filled up with flowering shrubs. Whose thick twisted roots are knotted in the rifts of the stones. At every step the aërial pinnacles of shattered stone grow into new combinations of effect, and tower above the lofty yet level walls, as the distant mountains change their aspect to one travelling rapidly along the plain… The blue sky canopies it, and is as the everlasting roof of these enormous halls.

“But the most interesting effect remains. In one of the buttresses, that supports an immense and lofty arch, “which bridges the very winds of heaven,” are the crumbling remains of an antique winding staircase, whose sides are open in many places to the precipice. This you ascend, and arrive on the summit of these piles. There grow on every side thick entangled wilderness of myrtle, and the [XXIV] myrtletus, and bay, and the flowering laurustinus, whose white blossoms are just developed, the white fig, and a thousand nameless plants sown by the wandering winds. These woods are intersected on every side by paths, like sheep-tracks through the copse-wood of steep mountains, which wind to every part of the immense labyrinth. From the midst rise those pinnacles and masses, themselves like mountains, which have been seen from below. In one place you wind along a narrow strip of weed-grown ruin: on one side is the immensity of earth and sky, on the other a narrow chasm, which is bounded by an arch of enormous size, fringed by the many-coloured foliage and blossoms, and supporting a lofty and irregular pyramid, overgrown itself with the all-prevailing vegetation. Around the rise other crags and other peaks, all arrayed, by the undecaying investiture of nature. Come to Rome. It is a scene by which expression is overpowered; which words cannot convey.”

Sublime as these environments were so sublime even was that stupendous effort of human genius, that astonishing lyrical drama now produced by Shelley, Prometheus Unbound. Nothing less is here aimed at than the portrayal of indomitable Resistance to omnipotent Force. Three types of vastest significance lay ready to the poet’s hand; Satan, Ahasuerus, Prometheus. The first two, awful forms of power though they be, yet are representative of a purely negative resistance. Their defiance, being prompted not by sympathy with mankind but by pride and will respectively, remains in consequence either barren to it or productive of evil. In Prometheus alone a Titanic Sufferer dares oppose himself for the love of a world in bondage to the dominion of an arbitrary but illimitable power. These were the appropriate conditions for the working out of the idea of man’s ultimate deliverance from subjection to Creeds and Crowns, as embodied in the dread shape of Jupiter, through the agency of the patient but deathless struggles of Prometheus, the impersonation of that ideal towards which the [XXV] supremely human tends to approximate. To say that the artistic handling of this poem is on the whole adequate to this infinite scope of its subject-matter, is to give it the highest possible praise; it can hardly however be averred that the requirements, of so tremendous a design have been completely fulfilled on all sides. Compared to the majesty of the first act, where the Titan’s pity of the Furies as they torture him reaches the utmost limit of moral elevation, the second act partakes too much of the character of purely poetic beauty, whose very excess of loveliness militates in some degree against the awful character of the action. Nor is the description in the third act of the liberation of the worlds and the marvelous change coming over it in consequence, wrought up to the intensest possible pitch of excellence: but on the other hand the choral songs of the conclusion, expressive of the same idea from a still more comprehensive point of view, as including the transformation not only all animated nature but the planetary orbs themselves, are of so transcendent a quality that they well-nigh appear as a rendering in language on the fabled music of the spheres.

In the summer of this same year 1819 Shelley with the rapidity characteristic of his genius wrote the Cenci, a work which conclusively proves that over and above his inimitable lyrical faculty he was possessed of a creative dramatic power second to it alone. Shrinking as a rule from the delineation in concrete forms of the dark and malignant passions of men, he here faces them under their most horrible aspect, and in the characters of Count Cenci and Beatrice has in a masterly way contrasted the moral deformity and hideous guilt of the one with the other’s light-like beauty and lofty gentleness; while the fearless energy belonging to both indicates their blood-relationship. The action throughout is of deep and vivid interest, the tragic passion and pathos culminating in such scenes as that of the banquet where Cenci offers a thanksgiving to God for the sudden death of his sons, or that heartrending one in the prison [XXVI] where the unfortunate victims of the hoary criminal after being convinced of his murder are informed of their doom, and the ensuing noble resignation of Beatrice casts over the lurid tumult of guilt and woe the ray as a final reconciliation.

Shelley, naturally desirous of procuring the representation of his drama on the stage, exerted himself to that effect chiefly with a hope that the excellent actress Miss O’Neil might undertake to appear in the part of Beatrice. But the manager of Covent Garden not only declined it, but on the account of the abnormal horror of its subject even refused to submit the character to her consideration, declaring himself ready at the same time to accept a drama by the author on a less revolting theme.

We must now retrace our steps in order to follow up the events of actual life which had occurred in the meanwhile. The sojourn in Rome had been embittered to the Shelleys by the loss of William their eldest now remaining child, a little girl Clara having died the year before. This misfortune was intensely felt by both parents, and Mary only began to be somewhat consoled when five months afterwards in November 1819 she gave birth at Florence to a son, the present baronet Sir Percy Shelley.

The resided for some months near Leghorn enjoying the intimacy of Mr. and Mrs. Gisborne. With the latter, an accomplished woman, the intimate friend of William Godwin in her youth, the poet studied Spanish, he subsequently translated the dramas of Calderon whose “Magico Prodigioso” revealed a new source of poetic delight. About the same time he was also much interested in the project of building a steamboat, the first that should have plied between Marseilles, Genoa and Leghorn. This was undertaken by Mrs. Gisborne’s son, an engineer, but after considerable sums had been embarked by Shelley in this enterprise it fell to the ground by reason of the Gisbournes’ abrupt departure for England, Shelley in the most amiable way making light of the loss thus incurred.

[XXVII] The latter part of the year 1819 was spent at Florence, where Shelley assiduously studied the works of art, recording in his own pellucid style his impressions of the statues that struck him most forcibly.

It was found however that the climate in Florence disagreed particularly with the poet’s health and the Shelleys therefore removed on the 26th of January 1820 to Pisa, which henceforce became their headquarters. This quiet old city with its half-deserted streets, its river, its near mountains and not distant sea seemed to possess a peculiar charm for Shelley, while the mildness of its climate and the quality of the water suited him physically better than any spot he had yet visited. It possessed another advantaged in the shape of Vaccà the celebrated physician, whose advice to Shelley was to abstain from all medicine. Another reason doubtless for becoming more stationary was the fear for their child’s health; for the benefit of which they moved in the spring to the Bagni di Pisa.

Shelley from thence during the hottest days of August undertook a solitary journey on foot to the summit of Monte San Pellegrino. On the three days immediately following this excursion he wrote the Witch of Atlas. This of all Shelley’s poems the most purely fanciful; it might indeed be called the Midsummer Night’s Dream of his imagination. Nowhere else does he give so unfettered a scope to the piece of work whose accumulated treasures of remote and exquisite imagery are embalmed in verse no less exquisitely delicate.

In the autumn of this year we find the Shelleys again at Pisa, and a circle of friends now gradually gathering round them; this on the whole appears to have exercised a beneficial influence on the poet’s health and spirits. Captain Medwin, his second cousin, old schoolfellow and ultimate biographer, had returned from India and settling at Pisa now saw a good deal of Shelley. It is to him that we owe a detailed account of Emilia Viviani, with whom the latter [XXVIII] now became acquainted. This unfortunate girl was the daughter of an Italian count, who having married again late in life, was induced by his wife, jealous of the remarkable beauty of her step-daughter, to immure her in the gloomy convent of St. Anne, until such a time as he should have fitted her with a husband. These facts, which Shelley learnt from the confessor of her family, roused his keenest sympathies and accompanied by the latter and Medwin, he went to see the poor captive; but his sympathy was heightened to rapturous admiration when he saw the Contessina herself, who with transcendent personal attractions and fine powers of mind was thus, in the flower of her youth, condemned to languish in dismal solitude. He as well as Mrs. Shelley henceforth visited her repeatedly, and obtained permission for her to return these visits during the carnival. They also corresponded and Shelley made unavailing efforts to obtain her liberation. She was afterwards married by her father to a man utterly unsuitable for her, and after enduring six years of a miserable wedded life the marshy solitudes of the Maremma, left her husband with her father’s consent, and died of consumption, brought on through broken-heartedness according to Medwin, in a tumble-down old Champagne at Florence. Such was the short sad career of her who inspired Shelley with Epipsychidion, that Apotheosis of Love inasmuch as that passion has become the last efflorescence of a few divinely inspiring natures. What the Song of Solomon is in the sphere of sensuous love, that is its most intense and exhaustive expression, Epipsychidion is to the most spiritual phase of this Protean passion, which perpetually changes its characters according to the nature it informs. In Epipsychidion the channel it had passed through was the highly subtilised of Shelley’s divine heart kindled to a white heat of ecstatic melody: the result is a matchless marvel of impassioned song, the emotions of which have become so rarefied that like the air of the High Alps it is found difficult to absorb so distilled an atmosphere.

[XXIX] Along with Epipsychidion we may mention Adonais written in commemoration of the death of Keats, which had taken place on the 23rd of February 1821 at Rome, as it was then erroneously believed in consequence of a savage attack on him in the Quarterly Review. Shelley always prone to generous admiration of contemporary genius, always ready to resent injustice and cruelty to others, was eager to testify to the world what he thought of the author Hyperion, and of his vile detractors, and that magnificent and most musical of Elegies Adonais was the result. In it he also finds occasion to render a splendid tribute to the genius of Byron, to whom he paid a visit at Ravenna in August 1821. Writing from thence to his wife he says one of the unpublished cantos of Don Juan, “It sets him not only above but far above all the poets of the day—every word is stamped with immortality;” and in allusion to a delicate task entrusted to him by Lord Byron he remarks, “It seems that I am always to have an active share in everybody’s affairs whom I approach.” As Byron finally determined to settle in Pisa he asked Shelley to look out for a palace for him, and in the autumn of that year he settled at the Casa Lanfranchi, while Shelley and his wife occupied a floor in the Tre Palazzi on the opposite side of the Lungarno.

The Shelleys had now plenty of society. They were on especially intimate terms with Captain and Mrs. Williams, who, according to the Italian fashion occupied a flat in the same house. Williams is described by Mrs. Shelley as gentle, generous and fearless, he shared with Shelley the passion for boating, and seems to have possessed some aptitude for poetry, for under the former’s auspices he was in time delivered for parts of a drama, to the delight of the poet, who compared himself to the sparrow educating the cuckoo’s young. Mrs. Williams was considered by Shelley, to realize his concept of the Lady of the Sensitive Plant which at once stamps her image on the mind’s eye as one of exceeding grace. A bond of the tenderest friendship subsisted between the poet and this lady to whom are addressed [XXX] many of the loveliest of his shorter lyrics, amongst others that aërially delicate piece, “the Lines to a Lady with a Guitar.” Another intimate associate at that time was Prince Alexander Mavrocordato, a Greek, full of ardent enthusiasm in the cause of his country, who on the 1st of April 1821 brought Shelley the proclamation issued by his cousin Prince Ypsilanti which declared that Greece should again be free. With what intense sympathy news of this kind was received by the poet may be imagined. He had already in 1820 celebrated the uprising of Spain and Naples in two Odes of consummate power and beauty. They are more especially remarkable for the impress they bear as of a soul possessed by a demonic rush and frenzy of inspiration, grappling therewith in breathless energy till exhausted with the spiritual stress and strain it droops under its melodious burden, seeming literally to suffocate with song. If the cause of liberty in any land could thus awaken in Shelley the highest chords of his genius, how did he kindle when the modern Greek “the descendent of those glorious beings whom the imagination almost refuses to figure to itself as belonging to our kind” shook off the stagnation of the Turkish rule in a noble endeavour after political independence! The lyrical drama, Hellas, Shelley’s last finished production of any considerable length, was founded on the events of the moment, and is by him called a “mere improvise.” An astonishing improvise to say the least of it, whose choruses, ranging from the softest sweetest notes of the lullaby to the trancelike harmonies of prophetic rapture, exhibit as in vision the struggle and triumph of the Greek cause, which represents to Shelley the vaster cause of the general progress of mankind. He was not himself destined to witness the realisation of a portion of his prophecy which took place a few years later, and in attempt at attaining which his friend Lord Byron lost his life.

We now touch on the last fateful year of Shelley’s existence, the year 1822. It opened auspiciously enough. Byron’s daily companionship was no doubt pleasurable, and [XXXI] his more serious conversation according to Shelley a sort of intoxication. The Williamses were friends after his own heart, and Leigh Hunt, to whom he was warmly attached, was expected to arrive with his family in the summer. This journey to Italy was chiefly undertaken by Leigh Hunt in consequence of a project suggested by Byron to Shelley during the latter’s stay at Ravenna, the pith of which was that they should establish a periodical paper in which Byron and his friends might publish all their original compositions and share the profits. Leigh Hunt, who had been the editor of the Examiner, a widely read paper of the time, seemed a fit person to join in such an undertaking, and Shelley strongly urged him, both in regard of the pecuniary advantages and literary luster to enter into such a partnership. For himself he deprecated taking any essential share in the concern both on account of the odium attached to his name, and because he neither wished to shackle the free expression of his opinions nor to injure the reputations and success of his friends by refraining from so doing.

A most welcome addition to this circle was formed by the arrival in Pisa of Captain Trelawny in January 1822. Of all those who from personal knowledge wrote about Shelley, he is the one who had most sympathetic insight and genuine appreciation of the poet’s lofty qualities. His manly straightforward description of the last months of Shelley’s life is simply invaluable, and while the picture it enables us to form tallies in many respects with the youthful outlines drawn by Mr. Jefferson Hogg, yet it commands itself at once to the judgment as possessing what the other fails in, a severe truthfulness and dignity in dealing with his subject. No other narrative brings us more directly in contact with Shelley than Trelawny’s picturesque sketch of his first introduction to the poet, and it is with the utmost reluctance that from want of space we refrain from quoting the entire passage. Trelawny on his arrival hastened to the Williamses’, when in the midst of animated conversation he saw a pair of glittering eyes steadily fixed on his, and Mrs. Williams [XXXII] observing the direction of Trelawny’s called out;—“Come in, Shelley, it’s only our friend Tre just arrived.”

“Swiftly gliding in,” to quote Trelawny, “blushing like a girl, a tall thin stripling held out his hands; and although I could hardly believe as I looked at his flushed feminine and artless face that it could be the Poet, I returned his warm pressure. After the ordinary greetings he sat down and listened, I was silent from astonishment: was it possible that this mild-looking beardless boy could be the veritable monster at war with all the world?—excommunicated by the Fathers of the Church, deprived of his civil rights by the fiat of a grim lord Chancellor, discarded by every member of his family, and denounced by the rival sages of our literature as the founder of a Satanic school? I could not believe it; it must be hoax. He was habited like a boy in a black jacket and trowsers, which he seemed to have outgrown, or his tailor as is the custom had most shamefully stinted him in his “sizings.” All possible doubt, however, was removed when at the instance of Mrs. Williams the pet read passages from his translation of Calderon’s Magico Prodigioso he was just then engaged upon, and which at once gave Trelawny a true touch of his quality. Suddenly as he had appeared he vanished and to Trelawny’s “Where is he?” Mrs. Williams said, “Who? Shelley? Oh, he comes and goes like a spirit, no one knows when or where.”

Two favourite pastimes of his youth were now resumed. We have already adverted to his practice of pistol shooting. This became now his daily relaxation in company with Byron, Medwin, Williams, Trelawny, and some others. They usually assembled at Byron’s residence and conversed till about three o’clock, when horses were brought to the door and the party after some hours “slow riding and lively talk” stopped at a small podere on the roadside. They then dismounted, had their pistols brought, and began firing. It was on such an occasion, as the usual riding party returned from their shooting, that a sergeant-major of dragoons dashing insolently through their midst, gave rise to a fray, in which [XXXIII] several of the party were wounded, Shelley being knocked off his horse in the act of interposing his body between the assailant and Trelawny. This affair, much noised abroad, became the ostensible reason for sending Byron’s best Italian friends, the Gambas, out of Tuscany, and resulted in his own removal to Leghorn.

Shelley’s other favorite pastime, passion would be the more appropriate expression, was boating. Water of whatsoever kind be it rivulet, stream, lake, but the sea above all, seemed to draw him to it as with a magnetic influence. He now, therefore, chose for his summer residence a lonely sea-washed house near Lerici on the gulf of Spezzia. This place was as wild as could be; the half-savage inhabitants sometimes on moonlit nights dancing among the waves and howling in chorus provisions only to be procured from a distance; the accommodation of the villa of the scantiest; all this however, so far from deterring, was an additional incitement to the poet for settling amid the soft and sublime scenery of this enchanting bay, and on the 26th of April 1822 the Shelleys and Williamses moved in consequence to the Villa Magni. Here, rambling about the country and seashore, or afloat on the tideless sea, Shelley in the society of congenial friends probably passed the most unclouded days of his life.

He was now engaged on the composition of the Triumph of Life, written in terza rima and deeply tinged by the splendours of land and sea by the glow and glare which alternating from gorgeous sunshine to gloom and storm especially marked that season. Fragment though it is, it ranks among the most quintessentially Shelleyan productions, possessing in the highest degree that power he had of clothing the most remote spiritual conceptions in forms of beauty or horror equally transcendent. In this marvelous effort to sound the depths of human existence the hand stopped midway—the painted veil was riven asunder—and to the question “Then what is life?” with which the poem abruptly closes, death responded. Other forebodings as of the [XXXIV] approach of destiny were not wanting at the time. Williams tells us that walking by moonlight on the terrace Shelley suddenly grasped his arm, and staring on the white surf on the beach, cried horror-struck “There it is again—there!” On becoming calmer he explained that he had seen a naked child (Byron’s daughter Allegra lately died) rise from the sea, and clap its hands as in joy smiling at him. Another time he terrified the entire household by his screams at midnight. He had seen a figure veiled and shrouded, which coming to his bedside beckoned him to follow. He did so; and on entering another room the phantom lifted the hood of its cloak and revealed Shelley’s own features and saying “Siete soddisfatto?” vanished. This was a fortnight before his death.5

The ill-fated boat, the Don Juan, which Shelley had ordered to be built for him by Captain Roberts at Genoa arrived in May, and the Hunts (eagerly expected) landing at Leghorn in June, Shelley and Williams started in their much admired boat to meet them. Besides themselves they had only a sailor boy, Charles Vivian, to man her. For in spite of Trelawny’s verdict that Shelley would be of no use, till his books and papers were hurling overboard, his wisps of hair shorn off, and his arms plunged in a tar-bucket up to the elbows, and his suggestion of consequent thereon of adding an experienced Genoese sailor to their crew, the two friends, in almost boyish glee at their natural performances, scouted the idea of additional help.

Shelley, inexpressibly delighted at meeting again with Leigh Hunt, accompanied him to Pisa, where he was installed in the ground-floor of Lord Byron’s palace. The latter, now fearful of the enterprise, was trying to edge out of it thus jeopardising Hunt’s prospects. He seemed, to Shelley’s infinite disgust, inclined to take his departure without coming to any definite arrangement with Hunt as to the share to be [XXXV] taken by him in the proposed magazine, which appeared under the title of the Liberal. In this review some fragments from Faust translated by Shelley with exquisite felicity, appeared.

Thus must dispirited, Shelley, after a few days’ delay in Hunt’s affairs, started from Leghorn in the Don Juan on Monday the 8th of July 1822. It was past one P.M. when he and Williams went on board, Trelawny, who was unfortunately prevented from accompanying them, watching them with a ship’s glass. Soon after starting the Don Juan was shrouded in a sea fog, the atmosphere became unusually sultry, and towards the evening a short but violent storm convulsed the lead-like sea, drove the vessels in shoals to the harbor, and Trelawny, startled from an oppressive slumber, long and anxiously watched for the reappearance of the Don Juan, but in vain. Two days of anxious suspense had elapsed when he rode to Pisa to communicate with Hunt and Byron. He remarks that when he told the latter “his lips quivered and his voice faltered” while questioning him.6

A search was immediately instituted and Byron’s yacht the Bolivar was dispatched to cruise along the shore; but it was not till the 22nd of July that the corpses of Shelley and Williams were discovered. The sorrowful task of acquainting the two wives of their terrible bereavement fell to Captain Trelawny. “As I stood on the household,” he writes, “my memory reverted to our joyous parting a few days before. The two families then had all been in the verandah, overhanging a sea so clear and calm that every star was reflected on the water, as if it had been a mirror; the young [XXXVI] mothers singing a merry tune, with the accompaniment of a guitar. Shelley’s shrill laugh—I heard it still—rang in my ears, with Williams’s friendly hail, the general bouna notte of all the joyous party, and the earnest entreaty to me to return as soon as possible.” And now he crossed their doorway once more the bearer of news that would overshadow two lives for ever. The misery of the days and nights which followed he declares himself unable either to describe or forget, over sorrows so irremediable the veil of silence is best drawn.

Shelley’s body had been found in deplorable condition near Via Reggio. It seemed as if he had been reading up to the last moment, for a volume of Keats was found in his pocket doubled back at the Eve of St. Agnes as if hastily thrust aside; he had also upon him a volume of his favorite Aeschylus.7 The body, hastily interred, had however according to Tuscan law to be burned as a safeguard against plague from objects cast ashore. This it was determined to carry out in the Greek fashion. Permission having been obtained from the Tuscan government Captain Trelawny procured all necessaries for the funeral ceremony, and at the appointed time Byron and Leigh Hunt arrived. The waste and solitary place bounded by the Apennines and the sea, the sun blazing down, the flames leaping up, thus the perishable part of an immortal genius ceased in fiery annihilation. Astonishing fact, the heart remained unconsumed! This Trelawny snatched from the blazing furnace, his hand being much burned in consequence. The ashes were then conveyed to the Protestant cemetery in Rome of which he had written on the occasion of his Elegy on Keats, now in its deeply prophetic strain far more applicable to himself, that it might make on in love with death to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place. They laid him near his “lost William” and Keats and the inscription on his grave runs as follows [XXXVII]

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Cor Cordium

Natus IV AUG MDCCXCII

Obiit VIII IUL MDCCCXXII

To which Trelawny added the lines from the “Tempest”

“Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.”

Mary Shelley returned to England in 1823 and survived her husband 29 years. Their son Percy Florence succeeded to the baronetcy on the death of Sir Timothy in April 1844.

Thus in his thirtieth year, still a youth in appearance, but with world-worn heart the author of the Westwind, the Skylark Epipsychidion and Adonais was snatched away; snatched away by that element he had loved so passionately, praying he might hear

“The sea

Breathe o’er my dying brain its last monotony.”

However sad and tragic this yet, yet how softly and solemnly is the short agitated life rounded by it! How was it secured for him beyond all other poets the dewy halo of perpetual youth! Truly while Shelley was writing his poems he was unconsciously acting a poem as transcendent. If his lyrics are divinely beautiful so is his life. And this to our thinking makes a study of him so fruitful. Others there may be possibly greater as pure artists. But he is a singer whose acts sand no less sublimely than his lips, whose every day existence moved as well as his thoughts and words to the sound of celestial music. If we would in an embodiment of flesh and blood seek for that haunting aspiration which lurks more or less dimly in the minds of all of us; if we would seek for a being in whom the spiritual tendencies completely triumphed over the more material parts of [XXXVIII] nature; in one word if we would seek the purely human stripped of all its grosser adjuncts and see as in a mirror how little less than angelic it is given man to be, let us turn with glad eyes and adoring hearts to Percy Bysshe Shelley.

No doubt a carping criticism may take exception at much in his productions; may complain of a “certain want of reality in the characters with which he peoples his glorious scenes;” of his “mystifying metaphysics;” of his failing or never attempting to attain to “completeness of form.” But all such cavillers would only prove that they never had penetrated into the inmost spirit of Shelley’s poetry, the characteristic excellences of which necessarily excluded certain others, the attributes of minds fundamentally opposed to his. In our opinion the true mental attitude towards one such as Shelley should be a deep and devout gratitude. He lavished his marvelous gifts so prodigally on a world that heeded him not that the least one can do is pay to his memory some portion of that enormous debt accumulating to him from his own to the present and future generations. For it should never be forgotten that poetry when it becomes the highest expression of the highest truths possesses a power for setting the soul in motion which at a time when traditional religion has lost its vivid actual hold on men’s minds, is simply the most sovereign promoter of the inner life. The mighty harmony of its inspiration enables thousands and succeeding thousands to soar to spiritual heights and kindle with spiritual fires unattainable, unimaginable save for such aid. What higher glory of the beneficent triumph of genius is possible on earth? and what poet has achieved such triumph more gloriously than Shelley?

NOTES

- Some interesting particulars about Dr. Lind may be found in Madame D’Arblay’s Diary. He died on Oct. 17, 1812.

-

According to Medwin, this translation comprised a portion of Pliny’s second book. It is very remarkable that one of the chapters included in it should have been that On God, in which the germ of much of Shelley’s subsequent speculation may be detected, and to which as if led by an irresistible fatality, he involuntarily (for the words are not his own) returns in almost the last of his productions:–

“I am now

Debating with myself upon a passage

Of Plinius, and my mind is racked with doubt

To understand and know who is the God

Of whom he speaks.”

Scenes from Calderon, SC. 2

-

A French author who seems to have influenced Shelley a good deal was Volny, whose famous Ruines appear to have produced a great effect upon him. The celebrated lines in Queen Mab,

“From an eternity of idleness

I, God, awoke,”

are almost a literal translation of “Dieu aprè avoir passé une éternité sane rien fair, prit enfin le dessin de produire le mond.” Les Ruines. Chapitre XXI. p. 123.

-

A glimpse of Shelley’s own feelings on this subject is afforded by the original reading of stanza VI, l. 6,7. of the Dedication to the Revolt of Islam. He had written,

“One whom I found (Harriet Grove)

was dear bit false to me,

The other’s (Harriet Westbrook)

heart was like a heart of stone.”

He perceived, however, that the allusions were too direct and personal, and with his usual delicacy softened the passage down to its present form. For this interesting detail not hitherto made public as well as other particulars contained in the foot-notes I am indebted to the kindness of Mr. Garnett.

- Shelley was himself the subject of supernatural legend. Lord Byron asserted, and seems to have actually believed, that a few days before his shipwreck, his phantom had been seen to enter a wood near Pisa.

- Mrs. Shelley and Mrs. Williams passed days of intolerable suspense. Mrs. Shelley unable to endure it longer hurried to Pisa, and rushing into Lord Byron’s room with a face of marble asked passionately, “Where is my husband?” Lord Byron afterwards said he had never seen anything in dramatic tragedy to equal the terror of Mrs. Shelley’s appearance on that day. Mr. Peacock, in Fraser’s Magazine, Jan. 1860. Shelley’s death by drowning is foreshadowed in the most startling manner in Mrs. Shelley’s novel, Valperga, written some time previously.

- Generally said to have been one of Sophocles, but erroneously.