The Art Weekly (April 19 1890): 70-71.

[Note: Blind wrote four pieces for The Art Review in 1890, when fellow poet and woman of letters Rosamund Marriott Watson was serving as editor. In addition to her review of Brown’s paintings, she published the following:

- “A Chain Criticism of the R. A.”–Link II” (May 17 1890): 102-103.

- “A Chain Criticism of the R. A.”–Link III” (May 24 1890): 111-112.

- “The Portraits of 1890” (July 12 1890): 165-67.

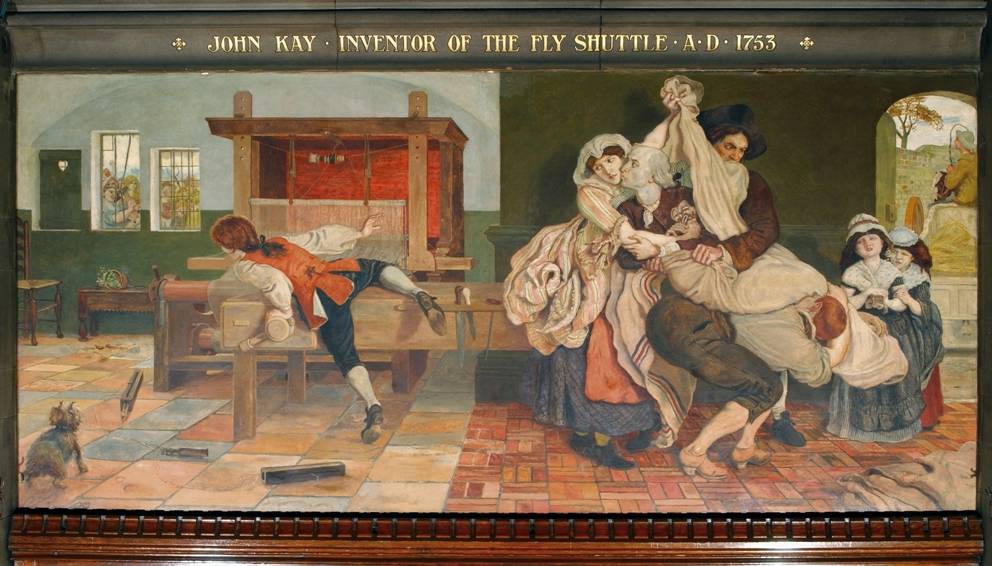

Blind’s close personal relationship with Ford Madox Brown, “the eldest of the famous Preraphælite brethren,” did not prevent her from mixing criticism with praise in her assessment of “John Kay, Inventor of the Fly Shuttle. AD 1753,” the tenth of the murals Brown painted for the Manchester Town Hall. After lamenting that Brown’s paintings and importance are now little known among London’s contemporary art students, Blind offers an extended critique of the John Kay painting, noting that its failings, “of the school rather than of the artist,” include “the exaggeration of the facial expressions, which at times verge on the grotesque.” She concludes, however, that “no art lover can afford to miss this latest exposition of a method which has had upon modern art an influence inestimable.”]

* * * * *

The time-honoured phrase, “Ars longa, vita brevis,” seem to lose all its meaning when we find ourselves before yet another new work by Mr. Ford Madox Brown, the eldest of the famous Preraphælite brethren, who, in spite of the passage of time and the death or secession of his fellow-workers, still pushes on with undiminished energy and unabated skill along the path which that enthusiastic band began long years ago to hew out for themselves through the hopeless wilderness of English academic art. Rosetti [sic], the pioneer, is dead; Millais has abandoned the minute elaboration and painstaking fidelity of his earlier method in favour of a freedom and breadth more popular with the paying public; but Madox Brown remains undaunted to body forth in practice the aims and objects of the sadly diminished company, and to show those of a younger generation what manner of painting it was that first set the art world laughing, drew them on to discussing, and ended by compelling both the admiration and respect of every thinking mind.

It is to be regretted that the perusal of this page of our art history is offered so seldom to the London student that to many Madox Brown can be nothing but an empty name, unassociated with any distinct idea of production, good or bad. In Manchester it is a name to conjure by, and there its owner has long since earned the reward of praise and pudding denied to him by the self-confident but somewhat thick-sighted metropolis. Regarding the small collection of his works now on view at Messrs. Dowdeswell’s Gallery in Bond Street, we reflect with annoyance, not unmixed with shame, that such examples of earnest and thorough workmanship are with us only for a while, and that they owe their existence to the enterprise and good taste of the corporation of that town of eternal rain with which the Londoner scornfully connects only smoke and manufactories, cotton and commerce.

The chief interest of this exhibition centers naturally in the panel just completed for the Town Hall in that city, where it will form number ten of such a series illustrative of the history of the country as London cannot boast.

The subject of the present picture is the attack by the weavers of Bury in 1753 upon the house of John Kay, the inventor of the hand-fly shuttle. This simple expedient enabled one man to do the work that formerly required two for its completion, and the wrong-headed mob, conceiving that this would deprive a part of them of their employment, arose in their wrath to destroy alike the work of offence and its creator. Kay narrowly escaped, owing to the presence of mind of his wife, who caused him to be smuggled from the place, wrapped in a blanket, by two staunch workmen and carried to safety in a cart.

This is the moment chosen for representation, and though the treatment is rather pictorial than literary, the story is well and clearly told. On the extreme right of the picture the waiting vehicle is seen through an open door, beside which stand two children—daughters of the threatened man. He, himself, wrapped to the breast in the blanket, is supported partly by a man who is engaged in completing his concealment, partly by his wife, on whose pallid cheek he turns to imprint a despairing kiss of farewell. A red-headed youth stoops to raise his feet from the ground, while his son Robert, half-lying, half-leaning on a table in the center of the apartment, watches the rioters, who are breaking in the window on the left, while he signals passionately with his right hand to urge the others to increased speed.

The composition and colours of the work are alike so excellent that we could scarce wish it changed, though the dramatic meaning of the scene would certainly have been enhanced had the angry throng without been less carefully subordinated. There seems a lack of sufficient excuse in their languid fury with its insignificant results for the terrified haste displayed by the principal figures, and the man whose carefully wielded sledge-hammer has shattered a pane of glass and upset a flower-pot suggests inevitably a well-trained super waiting for the end of the scene to make his entrance.

Apart from this intentional neglect of the full opportunity of the situation, it would be hard to find a better representative specimen of Mr. Madox Brown’s work, since it displays both the merits and the failings of his style. The former are so numerous and unmistakeable that we cannot spare space to speak of them at length; but the painting of the brick and stonework of the floor, of the figure of Kay’s son with his red waistcoat, of the agonized face of his wife, and of the stooping workman with his bare legs and ruddy head, must not be overpassed without brief mention. Of the failings, of the school rather than of the artist, the most conspicuous is the exaggeration of the facial expressions, which at times verge on the grotesque. This is particularly observable in the quite villainous face of the man supporting Kay, whose scowling black [71] brows, and flashing white gripping the edge of the blanket, give him a positively Japanese character of extravagant rage; and in the faces of the little maidens by the door, one of whom is on the pint of bursting into tears, is absolutely ludicrous. These two figures are, in fact, the sole blot on an otherwise admirable picture, and in one of them the foreshortening of the features, and the drawing of the arms, would admit of no improvement. Proper justice can scarcely be rendered to the work in its present position, removed as it is but a few feet from the floor; but no art lover can afford to miss this latest exposition of a method which has had upon modern art an influence inestimable.

The remaining four subjects are subjects of panels already in place, and need not again be described; but the visitor will find them well worth study in conjunction with the finished picture, both in comparison and contrast, with which they cannot but prove of the highest interest.

M.B.