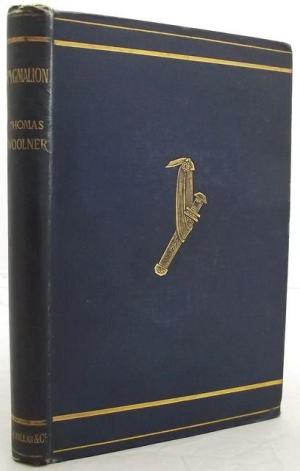

Pygmalion. By Thomas Woolner. (Macmillan & Co.) The Athenaeum, 24 December 1881, p. 843.

It may be said that there is always an advantage to an artist in laying hold of a type—a subject that, having already obtained currency, is full of associations that tend to vitalize it to the imagination. But, on the other hand, it is a dangerous thing to dress the clearly wrought classical myths in a modern garb, and to make them the vehicle of thoughts and sentiments not only foreign but often repugnant to their nature. The result of such an attempt is too frequently a sense of discord and incongruity. The reason of this probably is that the genius of Greece has already embodied its own conceptions with such supreme plastic power as to render all after attempts feeble by comparison. Even such a master poet as Goethe failed to some extent in his ‘Iphigenie.’ Compared with its Greek prototypes his rendering of the story of Agamemnon’s daughter is “as moonlight unto sunlight.” Contemporary English literature abounds in works of this pseudo-antique character, and amongst these the ‘Epic of Hades’ bears the closest affinity to Mr. Woolner’s ‘Pygmalion.’ The attractive versions of Hellenic myths which Mr. L. Morris has produced are marred by a want of directness, simplicity, and power; and in comparison with the ancient tales of demigods and heroes they appear like diluted renderings elaborately modernized and adapted for drawing-room reading.

Something of the same charge may be brought against Mr. Woolner. He has in a certain sense dislocated the well-known story of the fabulous sculptor who wrought a statue of such surpassing beauty as to become hopelessly enamored of it. A peculiar interest, quite apart from the literary merits of the poem, naturally attaches to the fact of so distinguished a sculptor as Mr. Woolner having chosen this subject. His treatment is exceedingly ingenious and clever, yet it lacks the suggestiveness of the pregnant old story, and tantalizes us like the face of an old friend through a mask.

Mr. Woolner represents Pygmalion as the son of a Cyprus chieftain, slain in battle against the Egyptians. He is tenderly watched over by his mother, a noble matron, under whose care twelve high-born maidens are likewise brought up in all feminine duties and accomplishments. It is the task of one of these, Ianthe, daily to carry fruit and wine to the work chamber of Pygmalion. One day, as she proffers the bowl to him, he catches a look of reverential awe in her upward-glancing eyes, such as Hebe might have worn when filling the goblet for Zeus. Then it flashes across his mind to perpetuate her look and attitude by carving a statue of Hebe from her. His mother’s consent being obtained, he sets to work; but however ardently he manipulates the marble, and however unflaggingly his model sits to him, there is always something lacking to the image, and what it lacks is life. At last, in moody despair, Pygmalion gives up all further effort, and resorts to the temple of Aphrodite to implore the aid of the goddess. She appears to him, promising life and immortality to his Hebe. Soon after Ianthe is asked in marriage of him by the warrior Orsines, and while wooing her for his friend the sculptor discovers that he and the maiden have long loved each other. In the first intoxication of this discovery he hurries with her to his mother, crying:—

O, mother, I

Have found her! Hebe she is come to life!

A rumor then gathers in the city that the statue, imbued with life by the goddess Aphrodite, had walked from Pygmalion’s work chamber to his house with the sculptor’s arms round her waist. The artist again sets to work on the statue of Hebe, and completes it triumphantly under the inspiration of love. But the celebrity he has won rouses the envy and hatred of the brethren of the craft, and it is whispered that Pygmalion has killed a maid and kneaded her blood up with the clay in order to make his stature live—a report which nearly leads to his own death.

This, in brief, is the tale of the new Pygmalion as retold by Mr. Woolner. One cannot help but thinking that, like one of the Euchemerists, he has set himself on the task of explaining on purely natural grounds the miracle of the vivified marble image.

The poem contains some very striking passages, and every now and then one finds an eminently picturesque image or a sounding and excellent line. Mr. Woolner’s knowledge of his own special art lends an added force and vividness to descriptions such as that where the maiden sits to the sculptor:—

Now daily came Ianthe to repeat

The posture for Pygmalion which he chose

For youthful Hebe when she filled the cup

Of Zeus. Hard was the maiden’s task, for she

Flinched not at tingling nerves and throbbing

Pulse;

Tho’ dizzy oft from the continual strain

Of keeping motionless. He, all absorbed,

Regarded her but as a beauteous shape

Aiding him in the God-like counterfeit,

Unconscious what she felt. Amazed each day

By fresh perfections dawning, he, each day,

More resolutely toiled. The gracefulness

And pride of her long rounded throat, his hands

Changed into awkwardness by mimicry.

The arches of her shoulders! Could he touch

On curves so exquisitely drooped, their sheen

Of movement tremulous! In despair he sighed,

Avowing it impossible for hand

To trace the lines in full variety

Throughout the space of that majestic breast;

Of dignity so peerless that if clad

In the great Virgin’s golden armor scales

They would but seem a suitable defence.

Mr. Woolner’s blank verse is generally smooth and flowing, but there are not any of these incomparable musical effects which poets like Mr. Tennyson and Mr. Swinburne produce by the aid of a great variety in their pauses and final sounds. Indeed, the final sounds in Mr. Woolner’s verse are often its greatest blemish; he frequently ends with words like “or,’ “in,” “as,” and “he,” a habit which, especially where the pronoun ends one line and the verb begins another, gives an unfinished appearance and irritates the ear by a flatness of sound. The following is a specimen of what we mean:—

Yet have I not seen one who strikes my soul

With sense of possibility that I

Could pas untired with her my lifelong course

Till now; when suddenly, as I saw her,

Ianthe, asking should she pour for me

I felt I could for ever with her dwell

And she would be my home. Therefore, as you

Are Lord and Guardian of her fate, I ask

Permission to declare my suit, and take,

If graciously received, the Maiden home

To cheer my mother with delightful hopes.

When at its best Mr. Woolner’s verse is distinguished by a lofty dignity and strength that make it resemble in some degree his own sculpture. Amongst the finest lines in the book are those in which some of Pygmalion’s work are described:—

Since the great Earth from Chaos first was hatched

And fledged herself in wonders sun by sun,

And moon by moon, no wonder held the light,

Filling the day with such resplendent awe,

As when the Titans armed with oaks, upwrenched,

And lumps of rock, enormous, forward moved

In even paces towards the huge assault:

And the Olympian Gods awaiting them

In range for action!

Brighter than clear noon

Shone Zeus; within whose hands quivered the bolts

Of thunder-fire flashing impatiently.

While on his right Pallas Athena stood

Well nigh as tall: her dreadful shield behind

Her thrown, its horrors toward the cliffs: Her spear

Looked a fixed star emitting baleful light.

He who made ocean tame, Poseidon, great

Earth-shaker, by his brother’s side, aloft

His ocean scepter held as he would crash

The rock-bound world. Ares his whole length lay

Watching the Titan’s march. And hovering round

The bird of Zeus hung darkly over all.

‘Pygmalion’ is hardly, on the whole, an advance on ‘My Beautiful Lady.’ The earlier poem has a spontaneity and a tender grace of sentiment which are less conspicuous in the present work; while Mr. Woolner seems to find a greater harmony of expression in lyrical measures than in blank verse. The perusal of ‘Pygmalion,’ like that of many meritorious poems, leaves the reader in a curiously divided frame of mind. Here is verse distinguished by any excellent qualities—such as good workmanship, subtlety of thought, refinement of sentiment, &c.—and yet there is a pervading sense of want somewhere. Byron asks, “What is poetry?” and gives up as hopeless; and if Byron could not define what poetry was, how difficult is the critic’s task! Can it be that Mr. Woolner’s tale, the work of a highly able, gifted, and disciplined artist, yet lacks that spark of vital fire, that harmonious inspiration, which Pygmalion sought to infuse into his Hebe, and which is of the very essence of poetry?