It took two years from submission to publication, but my essay on Elizabeth Robins Pennell’s biography of the pioneering feminist Mary Wollstonecraft is finally in print. It is featured in a new collection of essays on Pennell published by Edinburgh University Press titled Elizabeth Robins Pennell: Critical Essays, edited by Dave Buchanan and Kimberly Morse Jones. The volume appeared in April 2021.

As my essay argues, Pennell’s biography is actually two books. The first, published by the American firm of Roberts Brothers, appeared in 1884 under the title The Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. When the English publisher W. H. Allen bought the rights to publish an edition of the biography in England the following year, editor John H. Ingram “cut it down to our limit, viz. about two thirds of original size.” He did so without consulting with Pennell about these cuts. He also changed the title (to Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin) so as to subsume Wollstonecraft’s name under her husband’s surname. In response, Pennell took to the social media of her time — the letters section of the Athenaeum — to excoriate Ingram and disown this bowdlerized edition. “Though my name is on the title page, the book is not mine as I wrote it, and as it appeared in the American edition.”

And thereby hangs a fascinating, complicated tale. The book in which this tale appears is now available for online ordering, but here is a summary of my focus and thesis:

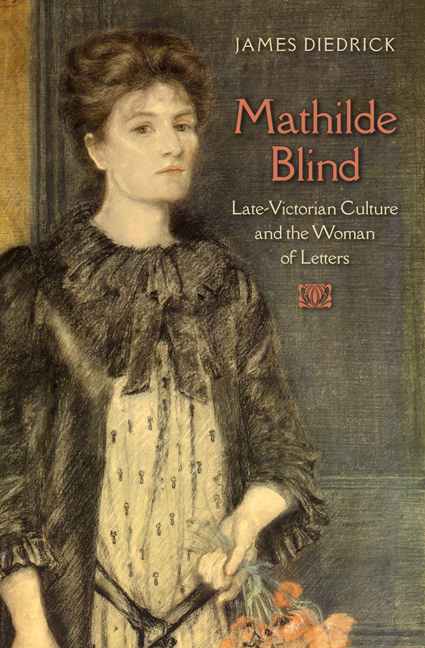

My essay analyzes Elizabeth Robins Pennell’s first book — the Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. I discuss its troubled passage into print in England, its equally troubled reception history, and how these troubles illuminate two larger, interrelated cultural phenomena. The first is the rise of professional women writers in the Victorian era, and their struggles with the male-dominated publishing industry, which Pennell’s experiences, especially with C. Kegan Paul and Ingram, exemplify. A related phenomenon—which the subject of Pennell’s first book renders inextricable from the first—is the turn to the republican politics and aesthetics of Romanticism among many late-century intellectuals and artists. Mary Wollstonecraft is central to both developments. She served as an inspiration to women of various political orientations seeking to gain agency and autonomy by the pen; she also inspired those who shared her radical ideas of social change. Since Pennell did not share Wollstonecraft’s radicalism, her biography met with far more resistance than she anticipated in its journey from Boston to London. It appeared in England at a time when women were in the process of wresting the narrative of Wollstonecraft’s life and work from the firm grip of male writers and editors who sought to make Wollstonecraft safe for the patriarchy, God, and country. Three radical women in particular—Mathilde Blind, Olive Schreiner, and Millicent Fawcett—wrote counter-narratives that to varying degrees challenged the “domestication” of Wollstonecraft, as well as Pennell’s role in this process. Pennell’s biography, its reception in England, and her subsequent essays on Wollstonecraft and the Woman Question offer a remarkable window on the contentious gender politics of late-Victorian England.

Mine is one of 12 commissioned pieces on various facets of Pennell’s writing career, including these notable essays:

- “The Modern Woman as a ‘Scholar-Gypsy’: Elizabeth Robins Pennell’s To Gipsyland,” by Holly A. Laird

- “The Gourmand as Essayist: Irony and Style in the Culinary Essays of Elizabeth Robins Pennell,” by Alex Wong

- “The Curious Appetite of Elizabeth Robins Pennell,” by Alice McLean

- “Elizabeth Robins Pennell as Early Champion of Popular Art,” by Kimberly Morse Jones

- “At the Museum comme a l’ordinaire’: Elizabeth Robins Pennell and Exhibition Culture,” by Meaghan Clarke

- “Elizabeth Robins Pennell’s War-time Prose: Nights and The Lovers,” by Jane S. Gabin

Update on July 9 2022: Lindsay Middleton (University of Glasgow) reviewed this volume for Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies, Issue 18.1 (Spring 2022)